Trinity Sunday May 30, 2021 St. Mary’s Episcopal Church The Rev’d Charles Everson Happy feast day to you! The feast of the Holy Trinity is the only feast in the church year dedicated to a doctrine, rather than a saint or an event in Jesus’s life. Today’s feast has roots in the fourth century when one of the earliest heresies surrounding the nature of Jesus Christ’s relationship with the Father – Arianiam – became rampant. Arius and his followers believed that the Son of God was created by the Father and was therefore neither coeternal nor of one substance with the Father. Out of that controversy, the Church prepared a suitable version of the Daily Office to be prayed in honor of the Trinity. This Office was often used on the Sunday after Pentecost (this Sunday), and like much of the liturgy we celebrate today, continued to develop over the centuries. On this day in 1162, Thomas Becket was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury, and his first act was to order that this day should be celebrated as Trinity Sunday throughout all of England. The observance spread rapidly throughout Western Europe until finally, in the 14th century, Pope John XXII declared that the Feast of the Holy Trinity be celebrated on this day throughout the entire Church.[1] While I thought briefly about explaining the doctrine of the Holy Trinity in great detail, I decided it might be easier to avoid heresy by defaulting to a symbol right here in our church that never seems to lose its flavor. There is a window just above the narthex doors, and you have to stand over here to see it. It’s much easier to see now that the old air conditioning unit in front of it has been removed. You can see a copy of it on the front of your service leaflet. The Shield of the Trinity shows us that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are all fully God by linking each of the outer circles – Pater, Filius, Spiritus Sanctus – to the center circle, Deus – “God” with the three connecting lines in which is written “est” meaning “IS”. Hence, the Father IS fully God, the Son IS fully God and the Holy Spirit IS fully God. The outer lines connecting the Three have written in them “non est” – “IS NOT”. Hence, the Father IS NOT the Son or the Holy Spirit, the Son IS NOT the Father or the Holy Spirit and the Holy Spirit IS NOT the Father or the Son. Each Person in the Godhead is each fully and completely God, one not more so than the other. But they are also distinctly unique from one another. This image shows us that the Trinity is all about relationship. God the Father is with the Son who is with the Holy Spirit who is with the Father, self-communicating, self-giving, self-receiving. When we profess belief in the Trinity, we affirm that it is of the essence of God to be in relationship.[2] Not only a relationship, but many relationships, beginning with the communion of the three Persons within the Godhead, and expanding to the relationship between God and all of creation.[3] How does this beautiful connectedness of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit manifest itself to us? St. John says in chapter 3 of his gospel, “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.”[4] The Son of God was eternally begotten of the Father and made incarnate by the Holy Spirit because of love. The loving relationship that exists between the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit isn’t meant to be merely observed from afar, the way we gaze upon a beautiful stained-glass window. The perfect state of loving communion between the three Persons of the Godhead is made known to you and me in the person of Jesus Christ, true God and true man. To use traditional theological language, God is not only transcendent, but also imminent. The God that St. Athanasius called “incomprehensible” in his creed wants to be intimately involved in our everyday lives. On Trinity Sunday, we aren’t just grappling with an abstract, theological idea. Rather, we are celebrating the relationship of self-sacrificial love that begins with the perfect communion of the three Persons within the Godhead, and expands to the relationship between God and humankind both in and beyond time.[5] In a moment, we will go unto the altar of God. The altar where God the Father communicates his love to us by giving us the precious gift of his Son by the power of the Holy Spirit via the recently anointed hands of a new priest. We are invited to bring ourselves, our souls and bodies, just as we are, to intimately encounter the God of the universe in a moment when we are somehow transported outside of time into God’s wider existence. As we kneel at the rail and receive the Almighty into our very selves, something happens. You’ve heard the expression, “You are what you eat.” The more and more we encounter God’s grace, the more and more we are transformed into the image of the One who created us…the One who humbled himself to share in our humanity, that we might come to share in His Divinity. St. Paul says, “And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another.”[6] Despite the fact that the doctrine of the Holy Trinity is difficult if not impossible to comprehend, on this great feast, in the words of the opening prayer, we “acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty…[we] worship the Unity.” The mystery of exactly what happens to the bread and wine at communion, and how it happens, is as much an inexplicable mystery as the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, and yet, it is perhaps at the rail as we intimately receive the body and blood of our Lord that the mystery makes the most sense. Amen. [1] http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15058a.htm [2] David Lyon Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, eds., Feasting on the Word. Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 47. [3] Full Homely Divinity. http://fullhomelydivinity.org/articles/Trinity.htm [4] John 3:16. [5] Full Homely Divinity. [6] 2 Cor 3:17-18. Ordination of the Rev’d Isaac Petty to the Priesthood

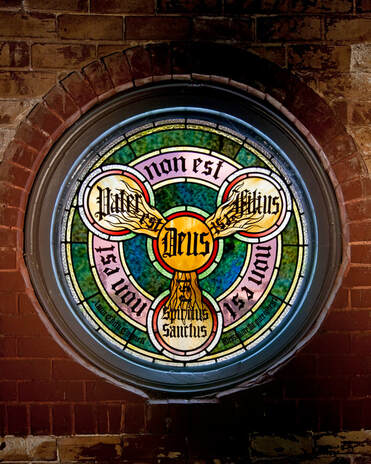

May 29, 2021 Isaiah 6:1-6, Psalm 43, Hebrews 4:16-5:7, John 6:35-38 The Rev’d Charles W. Everson Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral Good morning! What a joy it is to celebrate today with Isaac, our diocese, and indeed the whole Church. Today, Isaac will be ordained a priest. Later in the service, Bishop Field will address the good deacon and remind him that he is being called to work as a pastor, priest, and teacher. A teacher teaches things, and a pastor serves as the shepherd of his or her flock. I want to focus on why Isaac is being ordained a priest, and not simply a pastor or teacher. We Episcopalians are mostly unique amongst those whose heritage is in the Protestant Reformation in that we call the leaders of the local congregation priests and not pastors or ministers. This may seem to be a matter of semantics to cradle Episcopalians, but there is an important reason we do so: priests offer sacrifices, and pastors don’t. In today’s lesson from the letter to the Hebrews, Jesus Christ is referred to as a high priest. In the early history of the Hebrew people, Moses ordained Aaron as the first high priest, the one charged with entering the Holy of Holies on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, to make atonement for his sins and the sins of the people by offering sacrifices to God on an altar. At first in Israel’s history, the high priest’s status was secondary to that of the king, and his authority was limited to the religious sphere and specifically to the liturgical and sacrificial work in the Temple. Later, the authority of the high priest extended to the political arena. The office of the high priest and that of the monarch effectively became one and the same.[1] In today’s lesson and throughout his letter to the Hebrews, the author links Jesus not to Aaron, the first high priest of the hereditary Levitical priesthood, but to Melchizedek, a mysterious figure from the book of Genesis who pre-dates Aaron by six generations. Melchizedek is only mentioned twice in the Old Testament, but in short, he is described as having been anointed by God as both a priest and a king, offering bread and wine to God. In the late 1940’s, when the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in the desert caves of the West Bank, a manuscript from the 1st century BC was uncovered that indicated that the figure of Melchizedek had developed considerably in Jewish thought by this point. He was depicted as a heavenly redeemer figure, a leader of the forces of light, who brings release to the captives and reigns during the Messianic age. The author of Hebrews knows that his audience is familiar with both the Old Testament and intertestamental traditions when he declares that God appoints Jesus as high priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek.[2] The priests of Aaron became priests by their lineage, but for Melchizedek, there is no record of his family tree. He was appointed a priest by God to an order that had no beginning. Jesus is a priest forever according the order of Melchizedek, and thus the order has no end. The word order doesn’t mean Trappist or Dominican, it means after the manner of Melchizedek's priesthood. Later in this letter, the author goes on to make a sharp distinction between this order and the Levitical priests who continue to offer animals in sacrifice. They had to sacrifice millions of sheep, millions of goats and millions of cattle with millions of gallons of blood running down through the temple. Why? Because of the Golden Calf. Before that event in the life of the Hebrews, there was a clean, unbloody priesthood that Melchizedek represents, and as is recorded in the book of Genesis, Melchizedek’s priesthood included offering bread and wine. Since very early in the Church, a connection has been made with the bread and wine offered by Melchizedek as a foreshadowing of the bread and wine offered by Christian priests at the Eucharist. When Jesus was sacrificed on the cross, the priest and the offering were the same. But at the Eucharist, the priest and the offering are different, as it was with Melchizedek. The once-and-for-all sacrifice of the eternal great high priest on the cross is continued through Christian priesthood, a priesthood prefigured by Melchizedek’s offering of bread and wine on the altar, and perpetuated by thousands upon thousands of priests throughout history who have offered the same gifts on the altar in the name of Christ.[3] This point was driven home to me personally when I was ordained priest and opened so many cards of congratulations that said, “You are a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek.” St. Mary’s, the parish I serve and the parish that raised up Isaac for ordination, has a long history of offering the Eucharistic sacrifice every day throughout the year. When the pandemic hit last some 14 months ago, I felt it important to model the “stay at home” order, and so my bar at home became an altar and I learned the fine points of livestreaming. The Church has always taught that having at least one member of the Church Militant (meaning a living, breathing person) present at the Eucharist in addition to the priest is strongly preferred, so I had to think quickly who might be able to come over each day for Mass. It turns out that Isaac lived only a few blocks away from me at the time, and every day for nearly two months, he made the trek – sometimes by foot, sometimes by car – and was present for the Eucharist. I didn’t have to explain to Isaac why I needed to offer the Eucharist for the flock God entrusted to my spiritual care. He knew. And during those two months, I could see both his and my devotion to Jesus in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar deepen in those surreal-yet-life-giving moments at my bar-turned-altar. Like me, Isaac was formed how to be a pastor and a teacher in a different denomination. And like me, he owes a debt of gratitude to his former denomination for forming him as a disciple and follower of Christ. I know he feels this gratitude toward the Nazarenes, not because he’s said it explicitly, but because each year without fail, he sends me a joyful and almost gleeful text message to remind me of John Wesley’s commemoration in our church calendar. That said, I’m sure his feelings towards his former denomination vary wildly depending on the context. Yes, he owes them a debt of gratitude, but he also bears the wounds inflicted by some of their wounded individuals and power structures – wounds that are bound to heal over time but are ever fresh and painful. Isaac sacrificed much by making the decision to be honest about who God made him to be, the consequences of which rallied so many of his friends and colleagues both within the denomination and in ours to support him as a Christian and as someone called to serve the church as an ordained leader. He came to The Episcopal Church with both the academic training and quite a bit of experience as both a pastor and a teacher. But today, Isaac is being ordained into a priesthood that offers sacrifices, again and again. The Church doesn’t teach that priests re-sacrifice Jesus at the Mass. The crucifixion happened one time in history and can never be repeated. At the Eucharist, the priest offers to God a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving on behalf of the people, a bloodless sacrifice of bread and wine as foreshadowed by Melchizedek. This sacrifice makes the once-for-all sacrifice of Jesus on the cross present for us in our day and time. In the Eucharistic sacrifice, time stands still as earth and heaven are joined, and we are transported to that green hill called Calvary, and Calvary is brought here. And when we receive our Lord into our bodies, our sins are forgiven, our union with Christ and the Church is strengthened, and we experience a foretaste of the heavenly banquet which is our nourishment in eternal life.[4] Isaac, this is the priesthood into which you have been called. In a moment, when the bishop and the priests lay their hands on you and ask the Holy Spirit to make you a priest, you will be united with your Lord into an order that has no beginning and no end. The Holy Spirit will transform your diaconal character into that of a priest, giving you awesome power and responsibility to confect the sacraments which are the outward and visible signs of inward and spiritual grace. Your personality and your outward appearance will, of course, remain the same, but the Holy Spirit will transform your inner character to that of the Great High Priest. You will become an image – an icon – a visible manifestation of Jesus Christ in the world. Your hands will be anointed to signify this change, for by your hands, the bread of life and the cup of salvation will be consecrated, and by your hands, the people will be fed with the holy food and drink of new and unending life. A Bible will be given to you as a sign of your authority to preach the Gospel and administer the Sacraments. It’s not in our ordination liturgy, but a little birdie has informed me that you’ll be given a chalice and paten, the holy vessels of the sacrifice of bread and wine, signifying the continual sacrifice that you will offer for the sake of the people and indeed the whole world. As any of the priests in this room can testify, there will be times you will want to take off your priesthood. To undo what is being done today, just for a moment, whether it’s from fatigue, or because the collar around your neck limits your ability to say or do something as if it is choaking you, or perhaps because a parishioner has hurt your feelings and you can’t even imagine how you can continue to love them. In those moments, remember the weightiness of the hands placed upon you. And remember the grace given to you in that moment, grace that you will need as you offer yourself in sacrifice for the people until the day you die. Dear friends, let us give thanks to God for the gift of the priesthood, and for Isaac’s willingness to answer God’s call to sacrifice himself as a priest for the salvation of souls and the redemption of the world. Let us give thanks that by the Holy Spirit, the once-for-all sacrifice of Jesus on the cross is made present for us on this altar today. And when we receive our Lord into our bodies in the bread and wine of Holy Communion, let us give thanks to God for filling us with hope in this foretaste of the heavenly banquet which is our nourishment in eternal life. Amen. [1] Levine, Amy-Jill, and Zvi Marc Brettler, eds. The Jewish Annotated New Testament: New Revised Standard Version Bible Translation. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2017, 470. [2] Keener, Craig, ed. Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2019. 38. [3] https://www.hprweb.com/2018/09/christ-melchizedek-and-the-eucharistic-sacrifice/ [4] BCP 860. Pentecost Day

May 23, 2021 The Rev’d Charles W. Everson St. Mary’s Episcopal Church Acts 2:1-21 Happy feast day to you! And what a glorious feast it is in which we commemorate the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the fledgling Christian Church The earliest believers were together to celebrate the Jewish Festival of Weeks, or Shavuot, 50 days after the Passover. The Festival of Weeks celebrates the anniversary of the giving of the Law by God to the people of Israel on Mount Sinai in 1312 BC, an event for which Jews who were scattered all about the land regathered in Jerusalem. God’s ongoing presence in the world in the person of the Holy Spirit, long foretold by and promised by Jesus himself, begins with a vision of a reconstituted Israel. It’s not a reconstitution of the 12 tribes, but of a diaspora of Jews who live in all sorts of far-flung places, brought together for a common purpose. In this moment, God breaks in and announces Good News. It is fitting that on today’s feast of Pentecost, St. Mary’s begins a new chapter in our common life together at this phase in the pandemic by having our first meal and social event together) in over fourteen months (tomorrow after Mass). It is, of course, an incredibly happy occasion, but many of our parishioners are coming back to church after being fully vaccinated only to find new people they’ve never met. And more than a few of you became a part of this community during the pandemic and have never met some of our long-time members. St. Mary’s is a different community than it was when the pandemic began, and it will take awhile for everyone to get to know one another and find out what the “new normal” looks like. On that first Pentecost Day, the disciples and others heard a sound like the rush of a violent wind bringing divided tongues as of fire causing them to speak in other languages. When the Holy Spirit came upon the disciples, Luke says they were bewildered, astonished, and perplexed. “What does this mean?” they ask (v. 12). They mill around, stepping on each other’s toes, their faces reddening, their voices rising in confusion.[1] This confusion sounds just like the story of the Tower of Babel when in response to the people trying to build a tower tall enough to heaven, God confounds their speech so that they can no longer understand one another, and scatters them around the world. With the arrival of the Holy Spirit, the confusion of Babel begins to be reversed. Instead of widening confusion, there is a growing understanding, little by little. In this fantastical moment, divided humanity begins to come together in harmony as people speak languages other than their own and understand one another. The Holy Spirit continues to work in this way in our world today, and even here at St. Mary’s. Pentecost reminds us that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is for all people. No one is excluded. We humans like to erect divisions between ourselves, mostly to find ways to show that we’re better than others. Peter quotes the prophet Joel in his Pentecost sermon to indicate that God is pouring out the Holy Spirit on both sons and daughters, the young and the old – even the slaves representing those at the margins of society are included! The Roman imperial authorities allowed groups of people like the Hebrews the freedom to be themselves in most ways, but they required each of these linguistic and national groups to stay in their own silo as a way to control them. We do the same today in politics, religion, race, socio-economic class, national identity, etc, but the Holy Spirit powerfully unites those of us who acknowledge Jesus Christ as Lord despite our differences making us one body, one Spirit in Christ. St. Mary’s is not the same community it was in March 2020. But we are united by the Holy Spirit who has continued to work in and through each of us whether we were here in person or in quarantine. I can think of many ways in which I saw direct evidence of the Holy Spirit at work throughout the past year at St. Mary’s, in person, and in our online small groups, and perhaps especially in the many phone calls and porch visits between parishioners and clergy, caring for one another as best we can. As we begin to explore what the “new normal” looks like in the coming months, I encourage you to do a lot of listening. At the barbeque after Mass (tomorrow), have a conversation with someone you don’t know. Listen to how the Spirit has worked in his or her life over the past year, and tell a little about your story. Whether you’ve been at St. Mary’s 1 week or 12 weeks or 12 years, the Holy Spirit unites us in our common baptism into Christ’s death and resurrection, and continues to work in our midst. The Holy Spirit continues to break down barriers that divide us, bringing bring order and understanding to confusion and chaos. On this joyful feast day, let us pray for the grace to recognize the work of the Holy Spirit in our midst. And let us pray for the strength and courage to join in the Spirit’s work of breaking down human divisions wherever they exist, here at St. Mary’s, and in the world around us. Amen. [1] David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, eds., Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary (Louisville (Ky.): Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 19. Seventh Sunday of Easter, Year B

May 16, 2021 The Rev’d Charles W. Everson St. Mary’s Episcopal Church John 17:6-19 What does reading a mystery novel and going on a retreat at a monastery have in common? Both are forms of escape from the world. When you read a mystery novel, you get lost in the story, fantasize about the lives of the characters, and so on. When you go on retreat at a monastery, you’re at least supposed to disconnect from electronic devices and the world at large and spend time in prayer and meditation. In both cases, you get to escape from the world around you. We all need escape from time to time. We live in a world of constant pressures including complicated relationships, budgets, commutes, and other time constraints. It’s also full of temptation to sin, and oppressive societal pressures like sexism and racism and terrorism and the like. Since the beginning, Christians felt the need to escape from the world. We want to follow Christ with all that we are, and being in the world in the midst of temptations and those who challenge our faith can be exhausting. We’ve glimpsed a vision of what is good and holy, and have experienced genuine Christian community where we forgive one another and learn to love each other despite our faults. We even experience a foretaste of heaven each time we celebrate the Eucharist together. Some Christians throughout history have responded to this by living communally with likeminded Christians in monasteries or convents. On a smaller scale, many more occasionally visit monasteries or convents for a brief retreat from the world around us. In both cases, there’s an attempt in some way to “create a space, unencumbered by the world, that allows for a fuller realization of a faithful, holy Christian life.”[1] I remember back in my evangelical days when I was taught that allegiance to Christ meant avoiding certain movies, or abstaining from alcohol, or observing the rule that persons of the opposite gender couldn’t come in my dorm room as it might lead to an inappropriate sexual encounter. We were taught to avoid chunks of the world in order to be able to avoid becoming entangled in the world in such a way that living a faithful and holy Christian life isn’t possible. The early Christians who heard Jesus’s prayer from St. John’s gospel lived in a conflict-ridden world in which being a Christian resulted in persecution. I can only imagine that they fanaticized about escaping to a world in which the Roman Emperor became a Christian, got baptized, and stopped persecuting them. A world where practicing one’s Christian faith was seen as admirable. A world where it was easy to gather with other Christians to tell the stories of Jesus and regularly receive him in the bread and the wine. A world where simply being a Christian isn’t dangerous. This is the context of Jesus’s prayer. Note that it doesn’t include a request that they be allowed the luxury of escaping from this world. He instead asks the Father to protect them in his name.[2] Jesus acknowledges that he and his disciples “do not belong to this world.” (v. 14) But he specifically prays, “I am not asking you to take them out of the world, but I ask you to protect them from the evil one.” Christ didn’t call them into community to escape from the world, but instead to stay in the world under God’s protective care. We too are called to stay in this world, in the midst of the terrors of mass shootings, and nuclear weapons, persistent racism, gender inequality, and even a global pandemic. But to stay in the world under God’s protective care. We are called to live life amid all of the evil in the world without ourselves getting entangled in it.[3] The fuller realization of a faithful and holy Christian life cannot be found in escape from the world, but instead in dedicating oneself to God entirely while still being an active part of the world. In verse 17, Jesus prays “Sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth.” The word “sanctify” means “total dedication to God.”[4] This realization of holiness isn’t found in escape, but is found in the truth of God’s word – Jesus – as he is revealed in our world day in and day out. Remaining in the world is not without its risks. Being a Christian without being wholly dedicated to Jesus leaves us open to succumbing to the evil around us and getting off track. What does being totally dedicated to God look like in everyday life? The key is prioritizing one’s life by putting God before everything else, and more specifically by setting aside intentional time to pray and read the Bible. Our evangelical brethren call this setting apart of time to spend with God “a quiet time.” It was a time when one is supposed to read the Bible and pray. My problem was this: I often found myself wondering what part of the Bible to read, or what to pray. I would pray for my family, and those who were sick, and various church leaders, but after that, what was there to do? It was the discovery of what our prayer book calls the Daily Office that answered this question for me. In The Episcopal Church, the Daily Office consists of Morning Prayer, Noonday Prayer, Evening Prayer, and Compline with Morning and Evening Prayer being the primary and most important of the offices. These prayer services mark the hours of each day and sanctify the day with prayer. The Daily Office isn’t a magical thing to be done when you feel the need to escape, but it is a tried and true method to be sanctified in the truth. It’s all about prayer and the Bible, all tidied up and ready for you and I to use in our everyday lives. On the one hand, when I discovered Morning and Evening Prayer, I was grateful that the Church provided a systematic way to pray that has stood the test of time, and grateful that I no longer had to wonder how to proceed in private prayer; on the other hand, I no longer had an easy excuse when I didn’t know what to pray. The Daily Office may not resonate with you. There are plenty of organized ways to pray and study the Bible out there, both new and old. The important thing is actually making time to pray and read the Bible! If that’s not something you’re doing now – or have ever done in your life – don’t be scared! Take the plunge and give it a try! Spend five minutes in the morning in quiet prayer, beginning by praising God and thanking him for his grace, followed by a few minutes listening to God, and then ending with intercessory prayer for those you love. Jesus prays, “As you have sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world.” This is the opposite of getting out of the world! That said, we can’t escape the temptation to escape from the world. But Jesus is redirecting our desires today. We should look to “create a space, unencumbered by the world, that would allow for a fuller realization of a faithful, holy Christian life,” not by escaping from the world, but by dedicate ourselves to Jesus Christ while living our lives in the world under God’s protective care. We are called to live life amid all of the evil in the world without ourselves getting entangled with the world. In order to do this, we need to intentionally spend time with God in prayer by sanctifying ourselves in the word which is truth. One way to do this is by praying the official prayers of the Church in the Daily Office, but there are many other ways. We are called not to disengage from the world, but intentionally press into God while still in the world, and in so doing, we receive the grace and fortitude to live as a Christian in the midst of our broken world that we might have a more abundant life, right here, and right now. Amen. [1] David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, eds., Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary (Louisville (Ky.): Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 545. [2] Verse 11. [3] Feasting 547. [4] Michael D. Coogan, Marc Zvi Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, and Pheme Perkins, The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version : With the Apocrypha : An Ecumenical Study Bible. 4th ed. (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford UP, 2010), 1910. Ascension Day

St. Mary’s Episcopal Church The Rev’d Charles Everson May 13, 2021 As the psalmist said, “God is gone up with a merry noise, and the Lord with the sound of the trumpet.” According to the Scripture, on the very first Ascension Day, the Lord commissioned His Apostles to preach the Gospel to all nations; then, having blessed them, "he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight” (Acts 1:9). After all the disciples had been through with Jesus – the agony of his death, and the joy of his resurrection – it’s hard to imagine the sadness and despair they must have felt when he disappeared from their sight. The disciples saw him after the resurrection – they felt the marks of the nails in his hands and his side, and even ate with him – but now he’s gone. Not only is God gone up, humanity is too! For we believe that God humbled himself to share in our humanity in the incarnation of Jesus Christ at Christmas. Through the mystery of the Ascension of Jesus into heaven, we who are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs under the Lord’s table, are taken up with him. In the words of St. John Chrysostom, “Our very nature, against which Cherubim guarded the gates of Paradise, is enthroned today high above all Cherubim.”[1] Despite their sadness, the disciples were hopefully prepared as they heard their Lord tell say to them, “I will not leave you orphaned; I am coming to you. In a little while the world will no longer see me, but you will see me; because I live, you also will live. On that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you. They who have my commandments and keep them are those who love me; and those who love me will be loved by my Father, and I will love them and reveal myself to them.”[2] Unlike the disciples, we know how this plays out. Ten days after Jesus’s ascension, the Holy Spirit comes with power with a sound like the rush of a violent wind. Jesus keeps his promise and does not leave us orphaned. Though his body left this earth, by the mighty power of the Holy Spirit, he continues to work in the world today primarily in the Sacraments of the Church. By the power of the Spirit, when someone is baptized, they are cleansed from sin and welcomed into the household of God. By the power of the Spirit, the same Jesus who ascended body and soul into heaven on that first Ascension Day is the same Jesus who is here among us in the consecrated bread and wine. Let us give thanks that “God is gone up with a merry noise, and the Lord with the sound of the trumpet!” Let us give thanks to God for not leaving us orphaned. Let us give thanks that “when two or three are gathered together in [his] name, [he] will be in the midst of [us].” And let us give thanks that we are not alone – that God is manifesting his presence to us by the Holy Spirit in the face of the poor, and in the most holy Sacrament of the Altar. [1] Hom. in Ascens., 2; PG, 50, 414. [2] John 14. Sixth Sunday of Easter

Text: John 15: 9-17 Fr. Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 9 May 2021 The Gospel of John is often called the Gospel of love. The theme of love occupies a central place in the book. Perhaps the most-quoted Bible verse of all time – one that I am sure you have heard on many occasions – comes from the Gospel of John, and it is about love: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life” (John 3:16). But love is a broad term, an overused word in our society, with multiple meanings, everything from romantic and platonic love to fondness for puppies or ice cream. What does love mean in the Gospel of John? In our reading today, John connects love to friendship. Jesus tells the disciples who are gathered around him: “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:13). Ultimate love, according to Jesus, is sacrificing oneself for a friend. Jesus goes on to explain that the relationship between himself and the disciples is defined by friendship. They are bound together by love. And, as friends, Jesus has shared with them everything that he has heard from the Father. For the Gospel writer John, this section on the sacrificial meaning of love is a foreshadowing of Jesus’ Passion and Crucifixion. Jesus will soon set a personal example of ultimate love by laying down his life for his friends on the cross. In the Hebrew Bible, the paradigmatic story of friendship is that of David and Jonathan. As the young David rises in his military and political career at the court of King Saul, he becomes best friends with his son, Jonathan. So powerful is their friendship that we are told that Jonathan’s soul “was bound to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul” (I Samuel 18:1). When Saul sets out to kill David out of jealousy and hatred, it is Jonathan who arranges for his friend’s escape. When Jonathan dies on the battlefield, David mourns his death and declares that Jonathan’s love was “wonderful, surpassing the love of women” (II Samuel 26). Later, after the demise of King Saul’s family, David cares for Jonathan’s sole surviving son. Another beautiful story of friendship in the Hebrew Bible is that of Ruth and Naomi. Although Ruth is Naomi’s daughter-in-law, she goes beyond her familial duties, and the relationship becomes one of loving friendship. After the death of her two sons, including Ruth’s husband, Naomi plans to return to her home in Judah. The family had been living in the land of Moab following a famine in Judah. Now with her husband and sons gone, Naomi instructs her Moabite daughters-in-law to return to their natal homes. One daughter-in-law obeys and departs, but Ruth refuses to leave Naomi. She insists on accompanying Naomi to her homeland and adopting it as her own. Ruth proclaims her self-sacrificing love for Naomi with these eloquent and moving words: “Do not press me to leave you or to turn back from following you! Where you go, I will go; where you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die—there will I be buried” (Ruth 1:16-17). In the end, Ruth prevails, and she follows Naomi. Subsequently, Ruth marries a kinsman of Naomi, Boaz, and they become the ancestors of David. The Israelites were not the only people in the ancient world who celebrated friendship. The Greeks had a similar ideal of friendship. In the legend of Pythias and Damon, the former is accused of plotting against King Dionysius of Syracuse, and is sentenced to death. Pythias requests permission to go home to settle his affairs before the execution. When the king refuses, Pythias’ friend Damon steps forward and volunteers to be hostage until his friend’s return. If Pythias does not return, Damon is willing to be executed in his stead. The wait begins, and the king is suspecting that Pythias will not show up. But when he does return, the king is not only surprised; he is so moved by the friendship of the two men that he allows both to go free. The celebration of friendship seems to be a universal phenomenon. In China, for instance, friendship is considered one of the five cardinal human relationships according to Confucian philosophy. The foundational text for Confucianism, The Analects, begins with these words of the Master, Confucius: “Is it not a pleasure to have friends come visiting from afar?” The ideals and values of friendship manifest themselves across many different cultures and societies. To return to the Gospel of John, calling Jesus our friend is not just a metaphor. Jesus’ friendship is a lived reality. Jesus has many friends, for instance, the siblings Lazarus, Mary, and Martha. The Gospel of John says that “Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus” (John 11:5). He dines with them, and he chats with them. We can imagine him sitting in their home sharing stories and jokes, as well as his troubles and concerns. In other words, Jesus does not just go about preaching and working miracles all the time. He has a social life. Jesus’ friends provide him with companionship and support, and joy and love, and he does the same in return. Moreover, he makes himself vulnerable in his friendship. When Lazarus dies, he weeps. Toward the end of Jesus’ ministry, one friend betrays him, another denies him, and the rest take flight. Jesus’ experience of friendship was no exalted state of perfect bliss. On the contrary, it was subject to the same challenges and risks that we take on in our friendships. Jesus was fully human. One of the favorite hymns that I grew up with in my Presbyterian and Methodist family is “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.” It’s not in our Episcopal hymnal, though it used to be. The first verse goes like this: What a Friend we have in Jesus, All our sins and griefs to bear. What a privilege to carry Everything to God in prayer! O what peace we often forfeit, O what needless pain we bear, All because we do not carry Everything to God in prayer! The hymn is a wonderful profession of faith in Christ’s saving grace and power, all that he will do for us as a friend. But what the hymn seems to leave out is the fact that friendship is a two-way relationship. Jesus is our friend, but, at the same time, we are friends to Jesus. So, then, what is our role and responsibility as Jesus’ friends? How do we respond and reciprocate? In the Gospel of John, Jesus makes it clear: “You are my friends, if you do what I command you?” And what is this command, this condition for friendship with Jesus? He answers: “This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you.” And Jesus in his life and death shows us how to be a true friend. We are to offer each other up to Christ and to one another, and we take on the risks and vulnerability in the relationship. The friendship that Christ teaches and models is not about what we have to gain but what we are willing to lose. We may not be called to lay down our lives for Christ or for one another, but we may be called to give up our time, money, or other aspects of our lives that we value. Whatever the price may be, however, nothing can compare with the privilege of calling Jesus our friend.  Catacombs of Domitilla Catacombs of Domitilla Third Sunday of Easter Text: Luke 24:36b-48 Fr. Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 18 April 2021 In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus appears to his followers three times before his ascension to heaven.[1] First, he appears to Cleopas and another follower, who are traveling after the crucifixion from Jerusalem to the town of Emmaus. Jesus joins them on the road, but they do not recognize him. Only after he spends time with them talking and sharing a meal are their eyes opened (Luke 24:13-33). The second appearance is to Peter, but the Gospel only mentions the fact in passing and provides no description (Luke 24:34). Today’s reading is the third and final post-resurrection appearance. The disciples have gathered and are excitedly talking about the news of Jesus’ appearances when he suddenly comes to them. We can only imagine the shock and disbelief. In fact, the disciples can’t believe what they’re seeing. They think he may be a ghost, so Jesus shows them his hands and feet to prove otherwise. And then what follows is rather strange. The disciples are beside themselves with wonder and joy. They’re left speechless by what they are witnessing. Their master is not dead. He is alive. But what does Jesus have to say in the midst of this remarkable moment: “Have you anything here to eat?” I don’t know about you, but this strikes me as odd. He has just conquered death and come back from the grave. And in this extraordinary reunion with his disciples, he is looking for food. It seems so mundane and even silly considering the situation. Shouldn’t Jesus be responding with some grand gesture or profound saying? As strange as this scene may be, it has deep theological significance. In the context of the story, his eating the piece of broiled fish proves that he is not some disembodied spirit. He is flesh and blood. He has a body. He eats. Jesus’ resurrection from the dead is a physical reality. The scene of Jesus eating is repeated in other accounts of his post-resurrection appearances. On the road to Emmaus, the first recorded appearance in Luke, he joins the two followers for an evening meal. It is when he takes the bread, blesses and breaks it that the two men recognize Jesus. In the Gospel of John, Jesus appears to the disciples as they’re fishing, and he cooks the fish over a charcoal fire for them early in the morning (John 21:1-14). They have breakfast together. What is it about Jesus eating with his followers after the resurrection? It couldn’t have been just to satisfy his hunger after being dead for three days. Sharing a meal was a key part of Jesus’ ministry while he was alive. The Gospels are filled with stories of his eating and drinking. In fact, his ministry can be seen as beginning and ending with a meal. It began with the first miracle at Cana, where he turned the water into wine at a wedding feast and ended with the Last Supper. Jesus loved to gather at the table to share food, drink, and conversation. In theological language, he engaged in what we call “table fellowship.” And he practiced table fellowship not only with his family, friends, and followers but with perfect strangers. This scandalized proper Jewish society, which had strict rules concerning with whom one would eat and socialize. Sharing a meal with someone is an intimate act. Even today, we tend to eat with people with whom we are close or familiar – with those who are like us, family and friends. Think of the complicated politics of the high school cafeteria of who sits with whom. In ancient Jewish society, there were strict prohibitions against eating with certain groups, like the prostitutes and tax collectors. But Jesus flouted these exclusive norms and restrictions and practiced open table fellowship, welcoming all to his table. The table fellowship that Jesus established continues after the crucifixion and resurrection. But now the table fellowship is no longer just sharing a meal. The table fellowship becomes a Eucharistic event, an opportunity to experience the risen Christ in the flesh. It is no accident that in the post-resurrection appearances that he shares a meal with his followers. The meals are the contexts in which the disciples witness and experience the risen Christ.[2] The post-resurrection table fellowship of Jesus and his followers is a Eucharistic event. And it also points to what will come in the future – the Heavenly Banquet. One of the most interesting images of heaven in the Bible is that of the feast or banquet – a party. The book of Isaiah has this vision: “[T]he Lord of hosts will make for all peoples a feast of rich food, a feast of well-aged wines, of rich food filled with marrow, of well-aged wines strained clear” (Isaiah 25:6). And in the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus paints this portrait of heaven: “[M]any will come from east and west and will eat with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 8:11). Many people think of heaven as a hazy, quiet place with disembodied spirits aimlessly floating around, but we have this concrete, embodied image of heaven as a banquet, a feast. Whatever heaven might be, it looks like there will be banquets, where we will eat and drink, just as Jesus does after the resurrection. But it makes sense. In the kingdom of heaven, we will be unable to contain the joy of seeing God face to face. And think of all the happy reunions with our loved ones. How can we not rejoice and celebrate? The early Christians liked the idea of the Heavenly Banquet so much that they decorated their tombs with it. If I can direct your attention to the service leaflet, this is a wall mural from the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome. These catacombs contain thousands of underground graves of the early Christians. It may look, at first glance, like the Last Supper, but there are many more figures here than Jesus and his disciples – a couple of women, as well as some people waiting on the guests. It is a scene of the Heavenly Banquet. The Catacombs of Domitilla even has a large chamber at the entrance that served as a banquet hall, where families would gather to have a feast on the death anniversaries of their loved ones. The early Christians were a happy bunch! As the heirs of these early Christians, we, too, can also find hope beyond the grave when we will feast at the Heavenly Banquet. We will rejoice in the presence of Jesus, the host of the banquet, and we will be joined by all the saints who have come before us. But, in the meantime, we have a foretaste of the Heavenly Banquet in the Holy Eucharist. In our Book of Common Prayer, we have this prayer for Holy Eucharist during a funeral: Almighty God, we thank you that in your great love you have fed us with the spiritual food and drink of the Body and Blood of your Son Jesus Christ, and have given us a foretaste of your heavenly banquet. Grant that this Sacrament may be to us a comfort in affliction, and a pledge of our inheritance in that kingdom where there is no death, neither sorrow nor crying, but the fullness of joy with all your saints; through Jesus Christ our Savior.[3] Dear friends, Jesus Christ invites all of us to his table fellowship, here and now, in the Holy Eucharist, and in the life to come, in the Heavenly Banquet. Let us come to his table and rejoice in our risen Lord. Amen. [1] The Book of Acts, also believed to have been authored by Luke, suggests that Jesus appeared other times with “many convincing proofs” during the forty days before his ascension (Acts 1:3). [2] Gerald O’Collins, “Did Jesus Eat the Fish (Luke 24: 42-43)?” Gregorianum, vol. 69, no.1 (1988), pp.65-76. [3] The Book of Common Prayer (New York: Church Publishing, 1979), 498. Fifth Sunday of Easter, Year B

May 2, 2021 The Rev’d Charles W. Everson St. Mary’s Episcopal Church Acts 8:26-40; 1 John 4:7-21 In the reading from Acts, we continue to get a peek into the life of the early Church just after the resurrection of Jesus. Most scholars believe that the book of Acts was part of a two-part work comprised of Luke and Acts together, authored by St. Luke the Evangelist. St. Luke was a Gentile, meaning he wasn’t Jewish, and Luke-Acts is the only book in the New Testament written for a Gentile audience. Acts is a book written by an outsider for outsiders. The story begins with an angel telling Philip to go out into the wilderness. There, he encountered an Ethiopian eunuch who had come to the Temple to worship and was returning home. The differences between the eunuch and Philip are striking. First, the fact that he’s Ethiopian in 1st century Palestine means that he had much darker skin than the Hebrews. He’s of a different race. Second, he’s a foreigner from somewhere south of Egypt, which is largely an unknown place to the Hebrews. [1] He’s of a different ethnic background and nationality. And third, he’s a eunuch. In ancient times, a eunuch was a castrated male servant who was trusted to perform social functions for royalty. Essentially, they were neutered male human beings. As long as the deed was done before puberty, they were deemed safe to serve among women of the royal household. Despite this, eunuchs were stereotyped as sexually immoral people. His sexual state seems to be rather important to Luke as each of the five times he refers to the Ethiopian in this passage, he’s identified as “the eunuch.” The bottom line is that this Ethiopian guy was different in so many ways from both Philip and the earliest Jewish Christians. He was an outsider. He was reading the book of Isaiah when Philip ran into him. After reading the passage from Isaiah which we now refer to as “the Suffering Servant” passage, the eunuch asked Philip, “About whom, may I ask you, does the prophet say this, about himself or about someone else?” Christians today often say that Isaiah meant to refer to Jesus, but that’s not actually true. Isaiah, after all, died about 700 years before Jesus was born. We never hear Philip’s answer to the eunuch’s question. Instead, Luke tells us that Philip begin to speak, and starting with this scripture, he proclaimed to the Ethiopian the good news about Jesus. While they were riding along in the wilderness in the Ethiopian’s chariot, they came to some water. The Eunuch said, “Look, here is water! What is to prevent me from being baptized!” After hearing about the Good New of Jesus Christ from Philip and randomly seeing some water, this guy asks a theological question about why he can’t simply be baptized. The only response to his question was the baptism itself. In other words, nothing is to prevent him from being baptized. Baptism is the great Sacrament of inclusion. It is open to all, without rules or conditions. It’s open to black and white, young and old, rich and poor, gay and straight, cis-gender and trans-gender, Jew and Gentile. In this story, Philip listens to the voice of God via the angel, and when stumbling upon some guy who anyone in their right mind would consider a weirdo, he shares his faith with him. And this is the way the Christian faith has been passed on ever since. Person to person. Insider to outsider. And when the outsider decides to respond by asking to be baptized, the Church does so. In today’s church, there are those who believe there should be a lengthy catechetical process prior to baptism. Some believe that priests shouldn’t baptize people who aren’t thoroughly trained and prepared for what they’re getting themselves into. I fear that they’re missing the point entirely. “Look,” the Ethiopian said, “here is water! What is to prevent me from being baptized?” The answer is absolutely nothing. Immediate baptism: if it’s good enough for Philip, it’s good enough for me. If you have not been baptized and would like to be, come talk to me, and we get it scheduled soon. Baptism is the great Sacrament of Inclusion. It’s open to all without condition. Baptism is the great leveler of humanity. We all process back from the baptismal font the same as the person standing next to us. Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch are both baptized Christians, and yet are very different people. Baptism doesn’t erase the differences or remove their human individuality, but it serves as the beginning of the Christian life and the entrance into the household of God in such a way that they are equals. One of the things I love most about St. Mary’s is our diversity. I miss the Reception after Mass where it was common to see a young person who’s been here two months sitting next to an older person who has been here for decades, or the rich person chatting with the poor person, or the black person having coffee with the white person. These conversations can be gristly and rough around the edges at times as the two people are coming from completely different contexts and perspectives. But through our common faith in Christ, these sorts of relationships are not only possible, but are life-giving and beautiful, and have so much to offer our fractured and polarized world. When you encounter someone who is radically different than you, and open yourself up to talk about something as intimate as your faith, both of your lives are enriched, and your hearts are changed. Sometimes, we are afraid of people who are different than we are. That’s an instinctual human response. Fear is a powerful force, and it can lead to ignoring God’s voice when we are called like Philip was to go on a journey to which we don’t know the final destination. How can we overcome fear and say yes to God? Love. Not romantic love, not the love you feel for your parents or siblings, not sentimental love. The love we heard about our second lesson in John’s first epistle. The Greek word used throughout this passage is agape, love that gives without expecting a return, sacrificially. God is love, agape. Jesus died for us as an act of agape, and we ought to agape one another. In other words, friends, you and I are called to express outwardly what we have received personally from God – a sacrificial love that gives without expecting a return. Love in this sense isn’t an ideal to aspire to or an emotion we feel, it’s a tangible choice.[2] As we hear and respond to God’s call to share our faith with others, we will encounter fear. Let us respond to this fear with agape love, a sacrificial love that gives without expecting a return. Let us reach out to the outsider that is different than we are and share our deep and abiding faith in Jesus Christ. And then, when the outsider responds in faith, let’s bring them into the household of God in the waters of baptism. [1] David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, eds., Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary (Louisville (Ky.): Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 457. [2] Ibid 469. Sermon for 5 Easter B

May 1, 2021 St. Mary’s Episcopal Church Acts 8:26-40, Psalm 22:24-30, 1 John 4:7-21, John 15:1-8 Fr. Larry Parrish A very wise psychotherapist, that Mary and I had the pleasure of knowing, once said that “neurosis is wanting to be safer than we can possibly be.” I think of his words often, and I have especially thought of them during the past year with all of the environmental, political, and cultural upheaval in our own nation. Note that he didn’t say that neurosis is wanting to “be safe”. We all want safety and security, even those of us who have our “here, hold my beer” moments. We, most of us anyway, want a roof over our heads, food in the refrigerator, the prospect of a paycheck, and the ability to sleep without having to stay alert to danger. Granted, there are many who are denied some, or all, of these basic securities, but it is not unhealthy to want them or even expect them. We are always going to be confronted by situations that could do everything from upsetting our happiness to killing us, and we do well to recognized real, not imagined, risk and do what we can to mitigate it, while recognizing that it will not be eliminated. It’s something we do every time we drive our cars. It is an inherently dangerous activity, but we mitigate the risks by wearing our seatbelts, practicing good driving habits, and staying alert to hazards, including our fellow drivers, whom we hope are staying alert to us instead of their smart phone screens. Neurosis, on the other hand, is being so afraid of being on the streets and highways that we quit driving. There is a difference between acceptance of real risks and irrational fear, however. Fear comes from circumstances we cannot control, and, paradoxically, when we try to control those circumstances without clearly understanding them, we end up adding to our fears. Such is the circumstances in our country today. Everything from media ratings to gun sales have been ramped up by those who manipulate our fear(s). Truth is stretched to the breaking point, and often dispensed with all together. Real dangers have been added to, or supplanted, with made up dangers. Critical thinking is replaced by slander. A good many of the fears stoked today have to do with change. The climate is changing and the demographics of our country are changing and there are those who see these changes as a threat. Persons who are “not like us” are feared, stereotyped to the point of caricature, and even demonized. This is where our Christian faith comes in, though, it too is often twisted in the service of the fear of others. For as Christians, we are instructed by Scripture, to love one another, NOT fear one another. John the Evangelist, in his letter to the early Christian communities, and to us, says, “Beloved, let us love one another.” i.e., “You who are loved, love one another.” It is not just an admonition to love others, it is an important action of our faith, and witness to the God we say we believe and trust in. He continues, because love is born of God and knows God.” God is the source of our love, and defines what this love is for those of us who claim to be His followers, and the followers of the One in whom He embodied Himself in the flesh, in our shape and form: Jesus. “Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.” Just as God bore witness to Himself to humankind in Jesus –“God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world . . .” --so we bear witness to God’s love for everyone through our love for others as a hallmark of being followers of Christ. This is a good place to think about what this love spoken of in our Epistle today means. I am sure that all of you here have wrestled with the meaning of love defined in and by God and have a perspective. I will share mine, just in case it might be helpful! Of course you know that the word used for love in the New Testament is the Greek Agape, which means something more, and sometimes different, than the kind of love we have for our mother, father, spouse, children, or even our dog or cat! It is a love that doesn’t always grow out of affection, and is often willed in spite of our emotional inclinations of the moment. The best working definition I have found comes from psychiatrist Scott Peck, which he illuminated in a book which was once popular among the much younger selves of us Boomers, The Road Less Traveled. He defines love as “Desiring the Best for Another.” To love someone is to seek the best for them. Not necessarily that which is most pleasing or most comfortable for them, but that which is best for them. That which will make them most whole and most human (my interpretation here). Though not writing as a Christian at the time (he became one later) he gives credit for this concept to the New Testament use of love. “The Other” can be a “Them or Us”, “Not Like Us”, “Other” that is feared and that we defend ourselves against, even to the point of destruction of the other, or “The Other” can be the one for whom we desire the best for, whether it be physical, circumstantial, economic, emotional, or spiritual health, no matter how “unlike us” they are. We might differ on the definition of “best” in particular circumstances. How it will play out might remain to be seen. It is, however, our starting point and default position as Christians. “The Other” is never the enemy (even when he or she think they are!) they are the object of God’s love, and, therefore, of ours as well. Or maybe it is better said, “our love is the love of God which comes through us.” For this love does not come naturally to human beings. That is an important point to remember because we can become frustrated and discouraged if we try to generate this love on our own. St. John continues, “God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” If I might dare critique one of the profound authors within the New Testament, I think he is putting the cart before the horse here. It is because we abide in God that we can love! If St. John the Epistle author is also St. John the Gospel author, he knows the words of Jesus on the subject. In today’s Gospel, Jesus tells his disciples, and us: “Abide in me as I abide in you. Just as the branch cannot bear fruit by itself unless it abides in the vine, neither can you unless you abide in me.” These are words to be taken to heart as Jesus’ 21st century disciples not only as they pertain to our mission to love others, but to anything we undertake in which we seek to know, glorify, and serve God (and others). (To use an image borrowed from a recently read sermon)* The vine does not tell the branches to put grapes on its “to do” list, it just grow grapes! There are decisions we will have to make and commitments we must try to keep in our bearing the fruit that comes from loving others, but first we must remember that we are the branches of the True Vine. Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit, because apart from me you can do nothing. !!! We abide in Christ through our baptism, prayer, reading and meditating on the teachings and stories of the Bible, gathering together in worship, receiving the Sacrament, and risking love for others. The story from the reading from Acts today is an example of all of that. Besides, it is too good of a story to not, at least briefly, revisit. Philip, one of the first disciples of Jesus (The story of his call is in the Gospel of John), was someone whom we assume “abided in Christ.” He was there at the table when Jesus gave his “vine and branches” teaching which we received again this afternoon. He was undoubtedly in fellowship with the other disciples and followers of Jesus at the time, meeting with them regularly and eating bread and drinking wine “in His name.” From the story we can see that he was steeped in the Scriptures read by the early church (note: all Old Testament!), and by the teachings of Jesus, interpreted by Peter and other disciples. There must have been some awesome after dinner conversations back then! In doing all of this, Philip had made himself available to the Holy Spirit, the empowering and equipping Person of his—and our—Three Person God. The story tells of no particular intention of Philip. Just that as he was hanging out one day the Spirit tells him to “Get up and go” to a wilderness road. And as he was standing on that deserted stretch of 1st century highway, a chariot approached and Philip was told to stick out his thumb and get on board. There ensued a conversation with a Bible reading official of a foreign country. This Ethiopian Eunuch has been pictured as someone that good Jews of the time shouldn’t be associated with, his being eunuch and a “foreigner”, though contemporary scholarship disputes that. Whatever the case, he was either a high class outcast, or a person of power and privilege, and Philip was just a plowboy who had happened to hang out with, and continue to hang out with, Jesus. Philip tells him that the Scripture the Eunuch is reading says that God considers him loved and worthy of God’s sacrifice for. Joyfully, he seeks baptism, water is encountered, Philip baptizes him, and he goes “on his way rejoicing.” Next thing you know, Philip was walking through another strange neighborhood “proclaiming the good news to all the towns until he came to Caesarea. United Methodist Bishop Will Willimon, commenting on this story, says, “No triumphal, crusading enthusiasm has motivated the church up to this point, no mushy all embracing desire to be inclusive of everyone and everything. Rather, in being obedient to the Spirit, preachers like Philip find themselves in the oddest of situations with the most surprising sorts of people.”** So shall we. And we will not be afraid. In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen. *The Rev. Melissa Earley, in Living by the Word for Easter 5B, The Christian Century, online. **William H. Willimon, Interpretation Commentary on Acts, p.72 |

The sermons preached at St. Mary's Episcopal Church, Kansas City, are posted here!

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

To the Glory of God and in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Address1307 Holmes Street

Kansas City, Missouri 64106 |

Telephone |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed