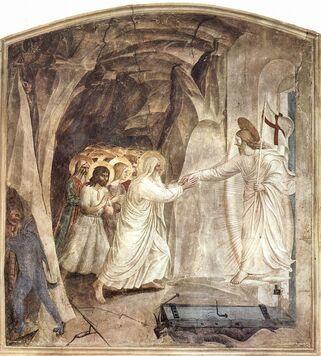

The tabernacle above the high altar. The tabernacle above the high altar. Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 25 December 2020 There’s been quite a shift from last night to this morning. Last night, our gaze was focused on a baby lying in a stable in the little town of Bethlehem. This morning, we behold a grand cosmic vision – the creation of the world by the Word of God, the Logos. Yet both scenes are about the same person – Jesus Christ. He is both the vulnerable little infant born to Mary and the all-mighty author and sustainer of the universe. In the mystery of the Incarnation, the divine and human come together. A lot of ink has been spilled over interpreting what we’ve just read in the Gospel of John. The fact that among the Four Gospels, it’s the only one that is given a fancy title, the Prolegomena or the Prologue, should give us some idea of how theologically significant it is. During the Seasons of Advent and Christmas at St. Mary’s, we conclude every Daily Mass with the reading of the Prologue. The idea that Jesus is the Word of God, the Logos, is not easy to understand. As one biblical scholar defines it, the Logos is “the logic that permeates and structures the universe, the divine reason that orders and gives meaning to all that is.”[1] Try explaining that at a cocktail party. We’re dealing with abstract Greek philosophy here. But, the fact is, we don’t have to understand the complex meaning behind the Logos to know God. Our faith is not based on grasping the nature of the divine reason or logic behind the universe. We can leave that to the theologians. Our Christian faith rests on the statement at the end of today’s reading: “And the Word became flesh and lived among us” (John 1:14). When we come to this sentence in praying the Angelus, we genuflect to express our deep reverence. In Jesus Christ, God became human. The Word became flesh. God became one of us and entered our world. Hence, God is not just an abstract, transcendent concept – someone up there beyond our comprehension. We can now know God through Jesus. Later in the Gospel of John, we find Jesus telling his disciples: “If you know me, you will know my Father also. From now on you do know him and have seen him” (John 14:7). Jesus is the incarnation and revelation of God. John, like the other Gospels, is an account of how Jesus, the Word made flesh, lived among the people of Palestine two thousand years ago. The Gospels describe and explain how Jesus revealed God through his teachings and ministry. After his death and resurrection, Jesus ascended into heaven, and we wait for his coming in glory and power at the end of time. But we also believe that the body of Jesus continues to be present here on earth. The Incarnation was not a one-time event that ended two thousand years ago. It is ongoing. Jesus lives among us. To go back to the statement “And the Word became flesh and lived among us,” the term that we translate as “live” is in the Greek actually “tabernacle” or “tent.” So a more literal translation would be “And the Word became flesh and tabernacled among us” or “pitched a tent among us.” Interestingly, we use the word tabernacle to refer to the box that contains the reserved host, the Body of Christ. So Jesus Christ, the Word made flesh, is present with us now in the tabernacle, and he will be present as we come up for Holy Eucharist. In the bread and wine of Communion, Christ will come to us in flesh and blood. One of my favorite Christmas carols is “God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen.” I just heard it on the radio this morning on my drive from home to church. I have come to especially appreciate the refrain: “Oh, tidings of comfort and joy.” I know that I am not alone in having experienced loss during the Season of Christmas. My mother died eight years ago around this time of the year. This season has never been the same since. But when I sing or hear this carol, I am reminded that Jesus came to give us comfort and joy. That thought consoles me and lifts my spirits. This year Christmas is not the same for any of us. COVID has wreaked havoc in our lives. We have all suffered losses. Yet, Christmas reminds us that God is not deaf to our cries of pain and suffering. In Jesus Christ, God became one of us to share our human lot and to give us hope and strength. This year, not all of us will be able to find comfort and joy in the presence of our family and friends. But we can all find comfort and joy in the presence of Jesus Christ, God Incarnate, who comes to us today as a baby in the manger and in the bread and wine of Holy Communion. Merry Christmas! [1] Judith Jones, “Commentary on John 1:1-14,” Working Preacher.  From the tabernacle above the altar in St. George’s Chapel just north of the high altar. Both altars were created by Tiffany and Company in New York using an endolithic process of infusing paint into marble by heat. When the artist Caryl Coleman died, jealous mosaic artists, fearing that the process would replace their craft, destroyed the patent, and Coleman’s endolithic process was lost. The altars at St. Mary’s are two of his nine creations. From the tabernacle above the altar in St. George’s Chapel just north of the high altar. Both altars were created by Tiffany and Company in New York using an endolithic process of infusing paint into marble by heat. When the artist Caryl Coleman died, jealous mosaic artists, fearing that the process would replace their craft, destroyed the patent, and Coleman’s endolithic process was lost. The altars at St. Mary’s are two of his nine creations. Christmas Eve Luke 2:1-20 The Rev’d Charles Everson St. Mary’s Episcopal Church December 24, 2020 Dear friends, unto us is born this day a Savior. Therefore let us rejoice and be glad. There is no place for sadness among those who celebrate the birth of Life itself. For on this day, Life came to us dying creatures to take away the sting of death, and to bring the bright promise of eternal joy. No one is excluded from sharing in this great gladness. For all of us rejoice for the same reason: Jesus, the destroyer of sin and death, because he finds none of us free from condemnation, comes to set all of us free. Rejoice, O saint, for you draw nearer to your crown! Rejoice, O sinner, for your Savior offers you pardon![1] That is an excerpt is from what is by far my favorite Christmas sermon, preached by Leo the Great, a fifth century Italian bishop. It has always brought me such joy, year after year. But this year, I read it through a different lens. Like all of you, my life has changed significantly since March when the pandemic began. Beyond seeing some of you from time to time with masks on from a safe distance, Jay and I have generally stayed home. This pandemic has been cruel, not only in stealing away our loved ones such as Dcn. Gerry, but in forcing us to isolate ourselves from our friends and family. As sad and depressing as this year has been for me, I can’t imagine what it has been like for those like my grandmother who have literally been alone for most of the pandemic. This year, when I read that old sermon by Leo the Great, I really wasn’t in the mood to rejoice and be glad. This year, when I re-read Luke’s telling of the birth of Christ, it wasn’t the latter half of the story with the all the joy – the part with the multitude of the heavenly host praising God – that caught my attention. It was the beginning of the story, with seemingly mundane details about a census. The emperor of the Roman Empire, whose name was Augustus, published a decree requiring that everyone in the Empire be registered as part of the census. The name of the local governor is given, as well as the names of several cities – Nazareth in Galilee, Bethlehem, etc. These were actual people in history, and places you can go visit to this day. Likewise, the Christmas Proclamation that we heard chanted before Mass captivated me with its poetic dating of the birth of Christ from nine different events. It situates the Incarnation within the context of salvation history, making reference not only to biblical events but also to the secular histories of the Greek and Roman worlds.[2] The specific time and place where Jesus was born was, quite frankly, a very dark period of human history. We can think of the Roman emperor the Dark Emperor in Star Wars, with Quirinius the governor as Darth Vader. Jesus was born into what you and I would call a police state that tortured people and denied most people basic human rights. It was brutal unless you were a wealthy, male, Roman citizen. The Jewish people suffered greatly under the heavy hand of Roman rule, and the trip that Joseph and a very pregnant Mary had to make from Nazareth to Bethlehem was arduous and fraught with danger and fear. Jesus was born into a world covered by a great cloud of darkness. On the one hand, it makes no sense that the God of the universe would enter into our world by such ordinary means in such an awful place and time. St. Leo the Great’s sermon helps us here. He continues, “For the time has come when the fulness of time draws near, fixed by the unsearchable wisdom of God, when the Son of God took upon him the nature of humanity, that he might reconcile it to its Maker. The time has come when the devil, the inventor of death, is met and beaten in that very flesh which has been his means of his victory.” Jesus took upon himself our very nature in time and history so that he could reconcile us to his Father – to begin to undo the damage done when our first parents chose to eat of the forbidden fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in that garden so long ago. The ordinary, mundaneness of it all is why Christmas isn’t a fairy tale. It is only because God chose to enter our world in history on a specific date, with other people who lived, and in places we can go visit that any of this makes sense at all. It is only after the ordinary details placing this story in its historical context that we hear the extraordinary story of the birth of Christ. This Christmas, you and I live in a world covered by a great cloud of darkness as we are in many respects at the worst point yet of this pandemic. Just as he met Mary and Joseph in their suffering and hardships on this day so long ago, God meets us here, at [TIME] on Christmas Eve in the year 2020 in Kansas City, Missouri. The extraordinary birth of Christ in all of its mundaneness gives us every reason, no matter our mood, to “rejoice and be glad. There is no place for sadness among those who celebrate the birth of Life itself. For on this day, Life came to us dying creatures to take away the sting of death, and to bring the bright promise of eternal joy. No one is excluded from sharing in this great gladness. For all of us rejoice for the same reason: Jesus, the destroyer of sin and death, because he finds none of us free from condemnation, comes to set all of us free. Rejoice, O saint, for you draw nearer to your crown! Rejoice, O sinner, for your Savior offers you pardon![3]” [1] Leo the Great, Sermo 1 de Nativiate Domini, slightly altered by me. [2] https://www.ncregister.com/blog/how-to-understand-the-christmas-proclamation. Accessed 12/23/2020 [3] Leo the Great, Sermo 1 de Nativiate Domini, slightly altered by me.  Fourth Sunday of Advent The Rev. Dr. Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 20 December 2020 Today’s sermon is the fourth and last in an Advent series on the Four Last Things. The first three were on Death, Judgment, and Heaven. And today I have the pleasant task of preaching on Hell. Needless to say, I haven’t been in a very festive holiday mood the past few days as I’ve been contemplating hell to prepare for the sermon. I know that some of you were raised in traditions that preached a lot about hell and damnation. I’ve heard horror stories about how some churches have traumatized people with the threat of hell for their sins or for their theological views or for their sexual orientation. There are many wounded souls out there. In terms of my own personal background, I was raised in mainline denominations that were at the opposite extreme. We didn’t talk at all about hell, and our conception of God was rather warm and fuzzy. So where do we Episcopalians, or more specifically Anglo-Catholics, stand on the issue of hell? Well, as with most theological issues, we have a broad spectrum of views in the Church and a great deal of room to believe what you choose. Some Episcopalians subscribe to the traditional conception of hell as a place of eternal torment for the wicked. There are others who reject the idea of hell altogether as incongruent with a loving God. What I would like to do today is to share with you what Scripture and tradition have to say about hell – a kind of history of hell, if you will, and engage in some reflections with you about the doctrine of hell. The ancient Hebrews believed that the dead went to a place called Sheol, also called the “Pit,” the “grave,” and Abbadon. In the Old Testament, Sheol forms part of a three-tiered conception of the universe with heaven above, earth below, and Sheol under the ground. It was a dark and dreary place where all the dead descended regardless of whether they were good or bad.[1] When the Old Testament was translated into Greek for the Jewish diaspora, the term that was used to translate Sheol was Hades, the underworld of the dead in Greek mythology. When we come to the Gospels, we have the term Gehenna that is translated as hell in English. Jesus speaks of Gehenna as the “hell of fire” (Matthew 5:22, 18:9) or the “unquenchable fire” (Mark 9:43). He also speaks of “the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 8:12). Gehenna or hell is a place of judgment and condemnation, where the unrighteous go to be punished. Recall Jesus’ parable of the “Rich Man and Lazarus.” Lazarus is a poor man who suffered from hunger and deprivation outside the house of the rich man, but, in death, he is carried by the angels to eternal bliss in the bosom of Abraham. On the other hand, the rich man, who, in life, had shown no compassion to Lazarus, is sent in death to hell where he suffers in agony amidst the flames (Luke 16:19-31). Christianity is not alone in having a place of punishment for the wicked. Most of the world religions, including Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism, have their equivalents of our hell. It seems to be almost a universal desire that there should be moral reckoning in the afterlife. In a moral universe, if there is no justice here on earth, surely there has to be justice in the life to come. For instance, it doesn’t make sense that the perpetrators of genocide and other crimes against humanity can live to a ripe old age while the millions of innocent victims suffer torment and slaughter at their hands. Where is the justice? One of the commonly held beliefs about hell in Christianity is that it is a place of eternal torment, that there is no end to the punishment for the wicked. But when we look further at Scripture as well as the tradition of the Church, there seems to be the hope of redemption even for those condemned to hell. In the Apostle’s Creed, which we proclaim at Daily Mass, and in the Athanasian Creed, we find the statement that Jesus “was crucified, dead, and buried. He descended into hell” (p.53). So, according to this phrase, during the three days that Jesus’ body was in the tomb, his spirit was in hell. And what did he do there? According to I Peter, Jesus “went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison” (I Peter 3:19-20) and that the Gospel was proclaimed even to the dead (I Peter 4:6). There are also similar references in the Old Testament – for instance, Psalm 49:15: “God will ransom my soul from the power of Sheol, for he will receive me.” Based on such passages from Scripture as well as the Creeds, a doctrine developed in the early Church, known as the Harrowing of Hell. The term “to harrow” is synonymous with “to descend” – so the “Descent into Hell” – but in Old and Middle English, it also has the sense of making a raid or incursion. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, this doctrine was expressed through beautiful religious art, such as the one on the cover of today’s service leaflet. It is a painting by the fifteenth-century artist Fra Angelico. I especially like the way it visualizes Christ’s descent into hell as a kind of raid. He’s carrying a military banner, trampling on the devils, and providing safe passage to the captive souls. Dear friends, we are drawing ever closer to the coming of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in Bethlehem. During the Season of Advent, as we wait and prepare for his coming, one of our rituals is to light the candles on the Advent wreath. And during Daily Mass, we have been concluding the service with the reading of the Prologue to the Gospel of John, which speaks of Jesus as the “light of all people,” the light that shines in the darkness and is not overcome by the darkness (John 1:4-5). There is much darkness in the world today – the suffering and death caused by COVID, racial injustice, political turmoil, poverty, crime. But no matter how dark it gets around us, the light of Christ will shine through. Indeed, that “light of all people” will penetrate even the darkness of hell itself. [1] The New Interpreter’s Study Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2003), 835-836. Advent III, 2020

The Rev’d Isaac Petty St Mary’s Episcopal Church, Kansas City I’ve seen a lot more death in recent weeks than I had anticipated seeing at this point in my life. I suppose it’s odd, being the son of a funeral home owner, that I have not been confronted with so much death before. However, I now find myself in patient rooms as they take their final breath, a holy moment that is accompanied by many emotions and family concerns. Saint Luke’s Hospital began, to overly simplify the history, out of the ministry of this parish nearly 140 years ago. I now serve there as a chaplain intern, and one of the kinds of visits I have all-too-frequently is pastoral care at the time of death or when care is withdrawn. Because of the pandemic, Covid-related deaths only add to the number of calls we receive and, being where we are culturally, a question both dying patients and their family members ask is to inquire about the nature of Heaven or to assure them of their heavenly destination. Fr. Charles spoke two weeks ago about death among the four Last Things in this Advent sermon series (with Judgment last week, Heaven today, and Hell next week). The recording of Fr. Charles’ sermon on death is out online, so I won’t rehearse what he said here, except to remind us that Christians have already died with Christ in baptism. Fr. Charles also referenced one of the prayers in our prayer book for use at the Commemoration of the Dead, which reads “life is changed, not ended;” and it continues, “when our mortal body doth lie in death, there is prepared for us a dwelling place eternal in the heavens” (BCP 349). Discussions of Heaven aren’t reserved for the time of death. In fact, heaven isn’t about us and our destinies so much as it’s about the will of the Maker of heaven and earth. Now, I do not claim to understand the architectural details of Heaven, and I truly don’t intend to turn this nave into a lecture hall, but I do intend to share what I think is compelling reason for us to start talking about heaven in our everyday life. Heaven is not about death, but it truly is about life. Scripture offers many different images for describing heaven and many books on many bookshelves are filled with speculations and interpretations. Put most simply, a common theme in the Bible is that heaven is God’s space, where everything is ordered according to God’s will. Heaven is filled with God’s holiness, which leads to several images, such as heaven being filled with light, the shining glory of God; and picturesque streets of gold, to show the richness of God’s royal kingdom; and depictions that it is filled with angels, whose job is eternally praising God. All of these depictions give us some idea of the kind of space God inhabits – one where everything is glorifying God and enjoying God forever, to paraphrase the Westminster Shorter Catechism. Our own Catechism teaches us that heaven is eternal life, and specifically the eternal life in which we enjoy God (BCP 862). You know, Jesus talked about eternal life. In one of the most commonly known verses of Scripture, Jesus tells Nicodemus that “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life” (John 3.16 NRSV). Jesus immediately follows this line with a discussion of light entering the world but humanity choosing darkness. The conversation between Jesus and Nicodemus concludes with Jesus saying “But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God” (John 3.21 NRSV). Deacon Isaac, what does all of this have to do with heaven? Good question! You see God is light, in whom there is no darkness at all (1 John 1.5), and we understand heaven to be filled with God’s light. But, thankfully, that light does not just stay in heaven. Appropriate for Advent, we are concluding the daily, Low Masses here at St. Mary’s by reading the beginning of John’s Gospel, including some of the verses in the Gospel I just proclaimed. This section of Scripture tells of the true light, coming into the world, to enlighten others. Likewise, the Creed we will say in a moment reminds us that Christ “came down from heaven.” Christ brought that heavenly light into the world and, as St Matthew tells us, he proclaimed that the Kingdom of Heaven had come near. Heaven and Earth are as different as night and day, quite literally, and yet heaven comes to earth. God’s light shines when heaven and earth overlap. Heaven may be a separate dimension that breaks into earth, our space. Heaven’s light, with its clean, pure, and loving reality becomes visible, even in our dark and sin-filled world, because of Christ’s presence. The work of Christ that began at his incarnation continues by the Spirit in the work of the Church as we await his coming again. At Christ’s impending return from Heaven, which we are especially mindful of during Advent, heaven and earth will be made anew, into one space, where nothing and no one is outside of the will of God, in which God is all-in-all, and all of creation is filled with God’s light. Heaven-on-earth is eternally filled with life and the glory of God. When someone on their deathbed asks me about going to heaven, I don’t often have the time to talk through four hours through a theology of the afterlife, but I feel comfortable talking about the joys of heaven that await them, because heaven comes to earth, and at the resurrection of the dead, heaven and earth will be one and all made anew. The Kingdom of Heaven will be the dominion into which the dead in Christ shall rise. As the Creed reminds us, not only did Christ ascend in heaven after his resurrection, but “he shall come again, with glory, to judge both the quick and the dead; [his] kingdom shall have no end.” The Good News for today is that we don’t have to wait for the day of the resurrection of the dead to experience heaven on earth. When the will of God is done, through glorifying God in the Church or by proclaiming the justice of God’s reign in the middle of an unjust society, we are catching glimpses of heaven coming to earth. In a few moments, after the bread and wine have been consecrated, we will join our voices in praying the prayer Our Lord taught us, asking for Our Father’s will to be done “on earth as it is in heaven.” Those gathered here will then commune with one another and the faithful from every age as we feast on Christ, who comes from Heaven and gives us that “grace and heavenly benediction” for which we pray. Those joining online will pray, too, for that spiritual communion, wherein God’s heavenly grace may be apparent as you prayerfully join in God’s ever-present embrace and see the glimpses of heaven made available to you where you are. May we all continue to grow in God’s “love and service” as we become “partakers in [that] heavenly kingdom.” Amen. Advent II

The Rev’d Charles Everson St. Mary’s Episcopal Church December 6, 2020 On this second Sunday of Advent, we find ourselves in week two of four in what is the closest thing to a “sermon series” that you’ll get at St. Mary’s. We are looking at the Four Last Things of Advent. We began with death last week, judgement this week, and then heaven and hell. Specifically, the final judgment that we say we believe in when we say the Nicene Creed, “and he shall come again, with glory, to judge both the [living] and the dead.”[1] We are given a vivid picture of this final judgment the old Latin hymn Dies Irae, arguably the most important hymn ever written in the West. This 13th century hymn was originally composed for the season of Advent, but ultimately became associated with funerals.[2] It begins heavy and somber: “Day of wrath, O day of mourning! See fulfilled the prophet’s warning, heaven and earth in ashes burning.” This is what the Day of Judgment will be like, when God’s wrath will be poured out upon all injustice and unrepented sin. As crazy as it sounds, the Church teaches us that the bodies of the dead will rise from their tombs at the sound of the trumpet, and they, along with all of creation, will answer to Jesus, the Judge and Lord of all. On this terrible day, we will all be judged according to our deeds.[3] When we face our Lord and Judge, we will be exposed before he whom this hymn calls “the King of tremendous majesty.” We won’t be able to hide our sinfulness, or our past, or our fears – all will be laid bare. Back in my Southern Baptist days, we talked and thought a lot about heaven and hell and things eternal, and the fear that the Day of Judgment evoked in me led to lots of guilt and shame. I lived in that guilt-laden world for far too many years. So hear me when I say that the Church’s call for us to reflect on the Day of Judgment isn’t a call to wallow about in fear and guilt. It is a call to prepare. Despite the Christmas lights and consumerism going on in the world around us, the Church calls us to keep awake and prepare for the coming of Christ in the manager at Christmas, in the bread and wine at Holy Communion, and at the last day. It’s a call to judge ourselves, lest we be judged by the Lord. It’s a call to examine our lives and conduct by the rule of God’s commandments and acknowledge our sins before Almighty God with full purpose of amendment of life. It’s a call to heed the words of John the Baptist, to prepare the way of the Lord and make his paths straight in our hearts, and turn from the selfish and sinful devices and desires of our own hearts. Advent is a call to wake up from our spiritual haziness and fatigue and prepare the way for our Savior. But beware of the risk of thinking that Advent means that we are called to clean ourselves up, or somehow by our own strength work our way to God. For judgment – whether it be our own self-judgment of our lives, or God’s judging of us at the last day – judgment leads to mercy. For the God who mercifully redeems us is the same God who judges us. And he uses the same means to both judge and save us: his unconditional love. God’s love has both effects – first judgment, then mercy. Advent isn’t about us pulling ourselves up by the bootstraps and being good enough to deserve God’s love, it’s about putting ourselves in a position – by prayer, fasting and repentance – by watching and waiting – to receive the unconditional love of God in Jesus Christ. Fr. Austin Farrer (Fare-er), a priest of the Church of England who died in the 1960’s and, ironically, came from the Baptist tradition, tells us how love leads to both judgment and mercy in his book “The Crown of the Year”. He says, "Advent brings Christmas, judgement runs out into mercy. For the God who saves us and the God who judges us is one God. We are not, even, condemned by his severity and redeemed by his compassion; what judges us is what redeems us, the love of God. What is it that will break our hearts on judgment day? Is it not the vision, suddenly unrolled, of how he has loved the friends we have neglected, of how he has loved us, and how we have not loved him in return; how, when we came before his altar, he gave us himself, and we gave him half-penitences, or resolutions too weak to commit our wills? But while love thus judges us by being what it is, the same love redeems us by effecting what it does. Love shares flesh and blood with us in this present world, that the eyes which look us through at last may find in us a better substance than our vanity. "Advent is a coming, not our coming to God, but his to us. We cannot come to God, he is beyond our reach; but he can come to us, for we are not beneath his mercy. Even in another life, as St. John sees it in his vision, we do not rise to God, but he descends to us, and dwells humanly among human creatures in the glorious man Jesus Christ. And that will be his last coming; so we shall be his people, and he everlastingly our God, our God-with-us, our Emmanuel. He will so come, but he is come already, he comes always: in our fellow Christian, in his Word, invisibly in our souls, more visibly in this sacrament. Opening ourselves to him, we call him in: blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord: O come, Emmanuel.[4]" [1] BCP 328. [2] Pope, "Sing the Dies Irae at My Funeral - A Meditation on a Lost Treasure," Community in Mission, June 10, 2015, accessed December 4, 2020 http://blog.adw.org/2011/11/sing-the-dies-irae-at-my-funeral-a-meditation-on-a-lost-treasure/. [3] Pope. [4] Christopher Webber, Love Came Down: Anglican Readings for Advent and Christmas (Toronto: Anglican Book Centre, 2002), 2-3. |

The sermons preached at St. Mary's Episcopal Church, Kansas City, are posted here!

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

To the Glory of God and in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Address1307 Holmes Street

Kansas City, Missouri 64106 |

Telephone |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed