|

Septuagesima

Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 28 January 2024 In the history of Christianity, the early church is the golden age. Beginning with the apostles and spanning the first four centuries of the faith, it is the age that produced the New Testament and the Creeds. It is the age that established the Sacraments and the Orders of Ministry. It is the age of saints and martyrs. In short, the early church laid down the foundations of the Christian faith. So, it is no surprise that we idealize the early church. During the Protestant Reformation, the early church was the model on which the various reforms were carried out. The reformers were trying to restore the beliefs and practices of the early church, purging what they believed to be the accretions and errors that had crept into the medieval church. But when we look closely at the early church, it was far from perfect. In today’s Epistle, we learn about a major source of division in the church at Corinth, meat sacrificed to idols. For the people of Corinth, meat was a luxury, expensive and hard to get.[1] One way to obtain it was to buy the meat sold in the markets after animals had been sacrificed in pagan rituals.[2] Or sometimes they could eat the meat in the dining area of the temple in which the sacrifices had been performed. Some Christians in Corinth had no qualms about acquiring meat this way, since they knew that the gods to which the sacrifices were made didn’t really exist and thus the rituals had no meaning. But other Christians, newer to the faith and steeped in the old pagan culture, refused to buy or consume it because of the association with the idols. The Corinthians could not resolve this disagreement on their own, so they appealed to the Apostle Paul. And what does Paul say? On the one hand, he agrees with those who believe there is nothing wrong with eating the meat, explaining that “we know that ‘no idol in the world really exists,’ and that ‘there is no God but one,’” (I Corinthians 8:4). But he doesn’t go on from there to force the other group into eating the meat. In fact, he doesn’t provide a simple answer. He offers a solution but with a condition. For those of you who believe that there is nothing wrong with the meat offered to idols, you can eat the meat but only if it doesn’t cause offense to a fellow believer. In other words, go right ahead and eat the meat in the privacy of your home, but if you risk being seen in a temple dining area, then don’t. Be sensitive to the conscience of those who disagree with you. Paul’s advice is not just a matter of being polite and considerate. It has profound theological meaning. If eating the meat causes another member of the community to stumble or fall, then it is nothing less than sin. It is a sin against that person whom you hurt. Moreover, it is a sin against Christ himself. For that person is just as much a member of the community of believers as you are, the believers for whom Christ died. Paul states, “Knowledge puffs up, but love builds up” (I Corinthians 8:1). The interpersonal relationship – love – is more important than correct knowledge or belief. The problem of meat offered to idols was one of many sources of division in the Corinthian church. They were also divided over issues of ethnicity – Jews versus Greeks, socioeconomic status – rich versus poor, and personal loyalties – Paul’s faction versus Apollos’s faction. We often bemoan how sadly divided Christians are today, but the early church was no model of peace and unity. Division in the church is nothing new. But, of course, the causes of our division today are different from those of the early church. Christians now have a whole host of new issues that have caused disagreements and conflicts, ranging from abortion to the blessing of same sex unions. And we also confront the bitter theological divide between conservative and liberal churches. I’ve heard horror stories of the trauma experienced by LGBTQ+ persons in conservative churches that have condemned and even expelled them. And, whether Roman Catholic or Protestant, many conservatives believe that the liberal churches, with their progressive theological and social views, as having abandoned traditional Christianity. At the other end of the theological spectrum, in liberal denominations, such as the Episcopal Church, we haven’t done such a good job either of showing love and respect to those who don’t agree with us. It is not uncommon these days to encounter the dismissal and even mockery of cherished beliefs and doctrines on social media and even from the pulpit. Several years ago, I heard the dean of a major Methodist seminary give a sermon at commencement in which he remarked, “Of course, none of us believe in the Trinity these days.” And a clergy friend shared with me the story of an Episcopal priest who at a diocesan gathering for Easter blurted out to her clergy colleagues, “None of you believe in this Easter stuff, do you? But it’s pretty ritual.” We wonder why so many people have left our denomination. My own personal background is mainline Protestantism, and my theological training has been at a liberal seminary. So, it is my own tradition that I am addressing. I value and celebrate the freedom of belief and practice in our mainline churches, but what I have found disturbing is the absence of sensitivity to those who do not share our views. We do not have to change our minds or compromise our beliefs, but at the same time, we should not be assuming a superior or condescending position to those who don’t agree with us. To borrow the Apostle Paul’s language, we should not be puffed up in knowledge. When I began serving at St. Mary’s five years ago, among the many things that I learned from Fr. Charles was a new term, “inclusive orthodoxy.” It refers to holding traditional Christian beliefs while having open and progressive views on social issues. Many of the younger Episcopal clergy have embraced this term, in part as a reaction against the extremes of the previous generation’s liberal theology. At St. Mary’s, we have many parishioners who would identify with inclusive orthodoxy. And we have others who would identify as liberal or conservative. This is the beauty of our Anglican tradition. We can hold a variety of theological and social views, but what is important is that we come to pray and worship together as one body. Soon, we will approach the altar and receive the Body and Blood of Christ. And in these Holy Mysteries, Christ comes to dwell in us – all of us, whether we are liberal, conservative, or inclusive orthodox; male, female, or transgender; white, black, or Asian. Knowing that Christ dwells in us, including the brother or sister with whom we disagree, how can we interact in any way other than love? [1] Jeehei Park, “Commentary on 1 Corinthians 8:1-13,” Working Preacher. https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/fourth-sunday-after-epiphany-2/commentary-on-1-corinthians-81-13-6 [2] Valéry Nicolet, “Commentary on 1 Corinthians 8:1-13,” Working Preacher. https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/fourth-sunday-after-epiphany-2/commentary-on-1-corinthians-81-13-3

Feast of Saint Cecilia

Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 21 January 2024 Today, we celebrate the Feast of Saint Cecilia, one of the patron saints of our church. We have a relic of Saint Cecilia – a bone fragment – on our altar, together with a relic of Saint Therese of Lisieux. After the service, at the end of the Postlude, you are invited, if you would like, to come to the altar rail to venerate the relic of Saint Cecilia. It is custom to touch, kiss and/or simply gaze upon the relic. Fr. Charles Everson, our former Rector, acquired the relics a few years ago. His selection of Cecilia should come as no surprise to us. She is the patron saint of singers, organ builders, musicians, and poets. Cecilia is a perfect fit for St. Mary’s! We have the best choral music of any church in the city, and our church is a premier venue for musical concerts and performances. Music lies at the heart of our identity. We have very few facts about Cecilia. According to the few ancient sources available to us, she was a young aristocratic Roman woman, who with her husband Valerian, his brother Tibertius, and a Roman soldier, Maximus, suffered martyrdom around the year 230 during the persecution of Christians under the Emperor Alexander Severus. The reason why she is associated with music is the story that as she lay dying with multiples blows of the sword to her neck, she sang to God. So, she ended her life singing, and, if I might extend the story a bit, she woke up in heaven singing in the arms of her Lord Jesus Christ. What an extraordinary story! And we can see why she was one of the most popular saints of the early church. But it is not just the dramatic story of her martyrdom that made her such a prominent figure. Her association with singing and music resonated deeply with the early Christians. Singing hymns was integral to worship back then as well as it is now. We have accounts from pagan writers at the time observing the strange practice of Christians singing at their funerals. So, why was Cecilia singing as she approached death? Why do Christians sing at funerals? To the outsider, it may seem odd, even crazy. But, for us believers, it expresses the joy of our belief that Jesus has conquered death and promises eternal life with him. We sing in defiance of the power of death. And we sing in defiance of death as well as anything that may challenge or threaten us. In the words of today’s Collect: “Gracious God, whose servant Cecilia served you in song: Grant us to join her hymn of praise to you in the face of all adversity…” Join her hymn of praise to you in the face of all adversity. We have nothing to fear because Christ has conquered death and all the forces of evil and sin. And in our pilgrimage through this life, as we struggle with the various personal problems and trials that confront us, he is with us every step of the way, giving us strength, courage, and guidance. Thus, the Apostle Paul calls on us to rejoice whatever situation in which we find ourselves: Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, Rejoice. Let your gentleness be known to everyone. The Lord is near. Do not worry about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God (Philippians 4:4-6). We can rejoice always because Christ is with us. Even in the darkest moments, the joy of our Christian faith is never extinguished. One of my favorite songs is the Gospel Hymn, “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” made famous by the singer and actress Ethel Waters. I remember seeing her on TV, singing it at the Billy Graham Crusades in the 1970s. In spite of Ethel Waters’s fame, she struggled with adversity all her life – poverty, racism, sexism. And yet in her later years, as she looked back on her life, she used her signature song, “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” as the title of her autobiography. She defined her life with the faith in the God who looks after the sparrow. I read the book when I was in high school, and it was a source of great inspiration for me. It’s time for me to read it again. I would like to share with you a few lines from the song: Why should I feel discouraged Why should the shadows come Why should my heart feel lonely And long for heaven and home Jesus is my portion A constant friend is he His eye is on the sparrow And I know he watches over me I sing, because I'm happy I sing, because I'm free His eye is on the sparrow And I know he watches over me Next Sunday, at 1:30 p.m., we will be holding a funeral for Ron Wiseley. Please keep his husband, Todd Chenault Wiseley, and the family in your prayers as they grieve. But in the midst of the grief, we will sing next Sunday as we say farewell to Ron. We will sing the joy of redemption and resurrection. Dear sisters and brothers in Christ, what are the adversities that you are dealing with at the present – sickness, the death of a loved one, financial worries, broken relationships? There is no neat and tidy solution to any of our problems. But, as people of faith, we have one sure source of strength and guidance that will never fail us, the presence of Our Lord Jesus Christ. So, on this Feast Day of St. Cecilia, in the midst of whatever adversities we may be facing in our lives, we join together, with our Patron, in lifting up our hymns of praise to God.

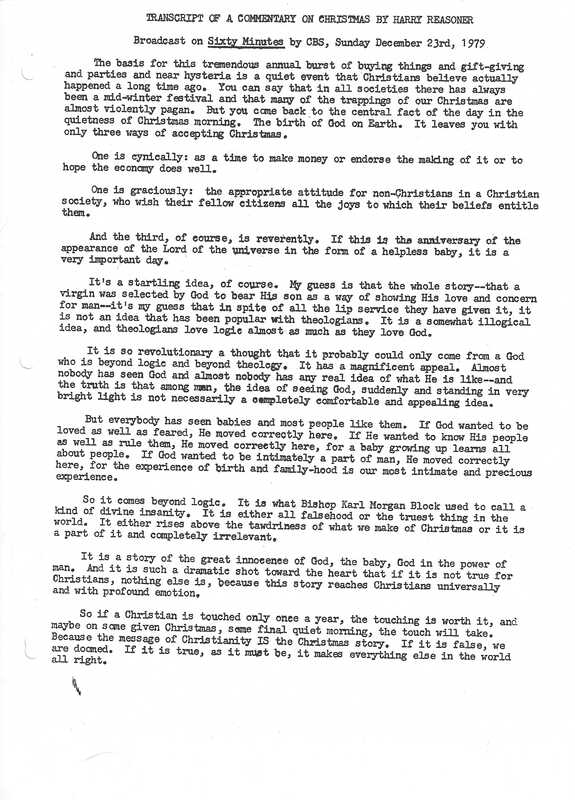

I am going to share with you an artifact from my past with you today. It is my Christmas gift to you. First, a little background is necessary.

My first son was born in 1976, 3 years after I graduated from Seminary. I was with his mother in the delivery room as he came out into the world. My first thought, as he began to cry, was what a miracle this was! He was cleaned up and placed into my arms. I looked at him and thought, “Anyone who doesn’t believe in God, should witness a birth!” Several years later was taking a three- day class at a Pastor’s Seminar. My memory of the content of the class is cloudy, and I couldn’t tell you what the professor from a United Methodist seminaries said those three days. But a handout he gave us at the beginning turned on the lights of Christian Faith and Tradition for me and I never forgot what it said. Mainly because I kept a copy! It was the transcript of the ending commentary of the legendary—to those of us at the time—TV news reporter and commentator, Harry Reasoner, at the end of the broadcast of CBS’s Sixty Minutes, on Sunday, December 23rd, 1979. THAT handout, or at least a copy of it, is the “artifact” I am going to read in a moment. I have made copies of it. You can pick up a copy as you leave by either entrance, if you wish. By the way, it really is an artifact. You will see from your copy that the handout was obviously transcribed using a typewriter and “printed” with a mimeograph! Here's the transcript of Reasoner’s commentary.

For those of you, if any, reading this from the St. Mary’s sermon archive, you will hopefully find it included with the sermon in the archive.

As I said. The lights went on. Of course, I had been schooled in the key Christian doctrine of the Incarnation. We affirm it in the words of the Nicene Creed each Sunday. “I believe in one God...and in one Lord Jesus Christ...very God of very God,...being of one substance with the Father by whom all things were made;...(Who) came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man.” However, all of that was still an abstraction to me, and I have never done well with abstractions. But when I read Reasoners words, I connected them with holding my newborn son in my arms, and it came together: Once upon a time, God had made Himself vulnerable to His creatures, so vulnerable that He manifested Himself in a baby. He who created the universe and all that is in it, put Himself into the arms, and at the mercy, of flawed human creatures. I thought of holding my baby son and realized what an astounding thing had happened when one day in history, that Christians commemorate as Christmas, God came into our world as a baby! To use Reasoner’s words, “it was a dramatic shot to (my) heart!” Harry Reasoner did not make this concept up. He was obviously grounded in the bedrock of Christian faith and Theology. Classic, Orthodox, Historical Christianity, has always held, that the baby of Scripture named Jesus, WAS GOD—incarnate: en-fleshed: “Embodied” in human flesh and blood. As the magnificent prologue to the Gospel of John, which is the Gospel reading for this morning, says, “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God. . . . And the Word became flesh and lived among us”. At this point it would be easy—or at least for me it would be easy—to wander off into the theological weeds and talk of how “the Son of God” is a different kind of “son” than any biological offspring of ours, and how “God’s Son” is different than “God the Son” and that would take us to the Trinity and . . . well, let’s not go there this Christmas morning. Let’s go back to the baby in Mary’s arms, who is also the Creator of All Things. This baby of the Christmas story is a real baby. Helpless and vulnerable. And yet able to call attention to Himself as babies can, with howls of hunger or discomfort (“no crying he makes” is a fiction made up by a song writer). He needs to be kept warm and fed and dry and protected from the elements and from Herod by the efforts, both mundane and heroic, of Mary and Joseph. And yet they hold God. Furthermore, the Baby represents a cosmic event that cannot be contained in a Bethlehem stable. NOT represents, but IS, what C.S. Lewis called “The Grand Miracle,” when he wrote that “the Christian story is precisely the story of one grand miracle, the Christian assertion being that what is beyond all space and time, which is uncreated, eternal, came into Nature, into human nature, descended into His own universe, and rose again, bringing Nature up with Him.” In this baby is a full-bodied sign that God is about redeeming us, our world, our universe, from the bottom up. Furthermore, if God could—and did—show up in our midst once upon a time as a baby laid in a manger, God can—and does—show up ANYWHERE! God showed up in the baby, in a minor country in the backwater of the Roman Empire, God the Jewish carpenter in Nazareth, God the teacher named Jesus, healing, telling stories and hanging out with people that aren’t approved by the powerful and the self-righteous, God the broken man tortured on a Roman cross, God the dead man now alive, fixing breakfast for his traumatized disciples. And God shows up in people we know, in places that are familiar to us, in family, in friends, in co-workers, and strangers. In people we love, and in people we can’t stand. He shows up in the bread and wine of the Mass, ordinary, mundane, pieces of Creation, that, nevertheless, hold the Creator. He shows up in us. He shows up in you. Not always with our knowledge or permission! And when He does, no matter what the time or circumstances, and when we recognize His presence, or point it out to another, it is Christmas.

Christmas Day

Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 24 December 2023 On this holy night, we greet the Coming of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. We join his mother, the Blessed Virgin Mary, his father, Blessed Joseph, the shepherds in the manger, and the hosts of angels in the heavens in unbounded joy and excitement. The eager waiting and anticipation of the past forty days of Advent has come to an end. The Messiah is here! In the Book of Isaiah, we read of the prophecy that foretold of the coming of the Messiah: “For a child has been born for us, a son given to us; authority rests upon his shoulders; and he is named Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6). The Prophet Isaiah proclaims this vision to the people of Judah in the face of a foreign threat in the eighth century B.C. The Assyrians have begun their invasion and conquest of the Kingdom of Israel and will later go on to attack the Kingdom of Judah and threaten its existence. In the centuries the preceded the birth of Christ, the Israelites experienced countless foreign invasions and endless political and social turmoil. In their desperation, they prayed for divine intervention, a Savior who would liberate them from the conflicts that tore apart their nation. They dreamed of a Messiah who would bring peace. In the Gospel of Luke, we find another expression of this perennial desire for peace. We read of the choir of angels who announce the birth of Jesus: “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace among those whom he favors!” (Luke 2:14). When Jesus was born, the Jews were suffering under the yoke of yet another foreign invader, the Romans, and social and political turbulence continued to plague the people. Jesus’ followers believed that Jesus was the Prince of Peace foretold by Isaiah, the fulfillment of the centuries-old prophesy. Today, as we celebrate Jesus’ birth, conflict in the Holy Land continues, as war in Israel and Gaza brings death and destruction. And we also have a long, protracted war in Ukraine. These are only two of the many conflicts that afflict our world today. Here, in the United States, we may not be in the middle of a war, but we find ourselves surrounded by our own set of conflicts: gun violence, racial tensions, political polarization and division in our national life. Then, there are the conflicts that we confront in our daily lives: road rage, bullying, office politics, church politics, broken relationships with family or friends. Peace seems ever elusive. But, as Christians, we place our hope in the Savior born in Bethlehem today, Jesus, the Prince of Peace. And as his followers, we share in his mission of peace to this turbulent and conflict-ridden world. There’s a song that I learned in Sunday School, and I’m sure you’re familiar with it as well. It goes like this: Let there be peace on earth And let it begin with me Let there be peace on earth The peace that was meant to be With God as our Father Brothers all are we Let me walk with my brother In perfect harmony Let peace begin with me Let this be the moment now. The song was composed in 1955 by Jill Jackson-Miller and Sy Miller. By the way, Jill Jackson-Miller was born in Independence, Missouri – where I grew up. Jackson-Miller, a devout Christian, composed the song during a difficult period in her life. She had become suicidal after the failure of her first marriage, but then she discovered what she called the “life-saving joy of God’s peace.” Our Lord Jesus offers this same peace to all of us. In the Gospel of John, Jesus promises his disciples: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you; not as the world gives do I give you” (John 14:27). The Apostle Paul later speaks of this peace that Jesus offers as the “peace of God, which surpasses all comprehension.” (Philippian 4:6-7). The peace of Jesus is beyond our human understanding and potential. To put it another way, it is a divine peace, God’s peace. As Episcopalians, we are reminded of God’s peace every time we gather for Mass. Soon, we will greet each other with “Peace be with you” or “Peace of the Lord.” And when we finish our service and go out into the world, we are often dismissed with the words: “Go in peace to love and serve the Lord.” Dear friends, what are the areas of your life where you need God’s peace? What are the ways in which you can work for peace in your community, the nation, and the world? As we celebrate the birth of Jesus, our Prince of Peace, may he grant you the peace in your lives that only he can grant. And may he empower you to the work of building his Kingdom of Peace on earth.

St. Mary's Episcopal Church, Kansas City

Third Sunday of Advent December 17, 2023 The Rev. Larry Parrish No nativity set ever had a figure of John the Baptist. Yet the flesh and blood original is there somewhere at the beginning of all of the Gospels, preparing the way for the appearance of Jesus. And he might not be a part of the Christmas Story as we call it, but he is a “must have” figure for Advent readings. According to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, he is the character that provides the introduction of the adult Jesus to a people that are waiting for someone to Make Israel Great Again, to restore the political kingdom that had thrived 500 years before under the great King David, and the great King Solomon. The writers of these Gospels go into some detail about who this “forerunner” was, what he looked like and what he said. John is found preaching a “baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (Mark 1:4 & Luke 3:3)) to those who gathered to hear him, and to amend their ways, telling them to “repent for the kingdom of heaven is near” (Matt: 3:2) and to “Bear fruit worthy of repentance” (Matt: 3:8 & Luke 3:8). He tells them that the Messiah is coming to “gather the wheat into his granary and burn the chaff with unquenchable fire.” Hie is described as one wearing clothes made from camel hair, his pants held up with a leather belt, and dining on locusts and wild honey. (Matt: 3:4 and Mark 1:6) Perhaps you have noticed over time that each of the four Gospels are unique, no one exactly like the other. This doesn’t invalidate them or make one more, or less, “true” than the others. It simply means that trying to describe who Jesus was and how God showed up in him takes more than one storyteller and one script. This is especially true of the Gospel of John, from which our Gospel reading came this morning. The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, share a lot of similarities. It is why they are called the Synoptic Gospels. They “sync” with each other. The Gospel of John is quite different in style and content than these Gospels. This is true from its very beginning, as it introduces John the Baptizer. In our Gospel reading from John today, John the Baptizer (NOT the same as John the Gospel Writer!) says nothing about repentance or doing righteous deeds; nor is described as wearing distinctive clothing and eating a distinctive diet. He doesn’t say anything about the restoration of Israel or the “Kingdom of God.” Instead, he is said to be a “witness to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him.” As in the other Gospels, John made quite a stir among the people he was preaching to –and baptizing--because some priests and deacons were sent from the Diocesan Office to ask him “WHO are YOU?” Stop! This isn’t a bad paraphrase, even if I do say so myself. It makes an important point regarding reading, and interpreting, The Gospel of John. The text reads “the Jews sent priests and Levites from Jerusalem.” John the Gospel writer makes use of the term “Jews” quite often and this has caused all sorts of mischief, feeding the warped perspective of anti-Semites throughout history. Most scholars agree that John’s use of “The Jews”, in its Greek form (hoi-Ioudaioi) doesn’t refer to the ethnicity, nationality, or the religious practices of the Jewish people.” It refers instead to “the religious authorities;” i.e. those in charge of keeping order in the institutional Temple (that can just as easily be read. “The institutional Church!”) That responsibility is not damning in and of itself, unless those holding it use their religion and its structure to have and keep power for very human reasons. Unfortunately, there have been and are many instances throughout history, and in the news today, in which Christian religious authorities have indeed over-used and abused their power. Enough said. Back to John. So, the emissaries of the religious authorities of the time asked John. “Who are you?” “I am not the Messiah.” “We didn’t ask you who you weren’t. Who ARE you? Are you Elijah?” “Nope.” “Are you the prophet?” (Maybe a reference to Moses cf. Deuteronomy 18:15) “Not even!!” “Look. Whoever you are. We have to take an answer back to the people who sent us. What do you call yourself?” John answered, “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness, ‘Make straight the way of the Lord,’ just like the prophet Isaiah said.” What kind of authority do you have to foretell the coming of the Messiah or the restoration of Israel?! Who ordained YOU!? “I am not foretelling either of those things. “I simply baptize with water” and tell anyone who will listen that, ‘Among you stands one whom you do not know, the one who comes after me; I am not worthy to untie the thong of his sandal.’” This is what I hear: John says he is not a prophet like Isaiah, but he is a voice such as Isaiah spoke of. “A voice crying in the wilderness, making preparation for the coming of God, who already stands among you as one who you do not know.” In John’s Gospel, God is not about the restoration of a human kingdom, but the restoration of the Cosmos, the Entire Universe, and the redeeming of all in it. What is to appear—in fact has already appeared (!)—is not a “what”, but a “Who,” the one “Who” has shown up in the midst of 1st century Palestine and continues to show up still, everywhere! I cannot isolate this Advent text about John from the five verses that precede it, or the six verses the follow it. All together they make up the Gospel text for Christmas morning. So on this Advent morning we have a glimpse of Christmas Day: To point out some of them: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” “What has come into being in him was life and the life was the light of all people.” “He was in the world, and the world came into being through him; yet the world did not know him.” “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us . . .” I don’t think that John of the Jordan knew this message in full. Whoever he was, he knew of the prophet Isaiah, so it’s a good bet that he knew the Hebrew Scriptures and the things that the people of the former kingdom of Israel longed for. But now, however, it happened, he knew that God was about to take action not to restore an earthly kingdom, but to share His life and “light” with all people—and that his mission was to point out the one who was make this message known through his own earthly body, life, and teaching. “He (John) was not the light, but he came to testify to the light.” And to do that pointing out, to testify, he had at his disposal, his voice. St. Augustine (Or was it St. Francis?) was said to have said. “Preach the Gospel always; and, if necessary, use words.” There is some wisdom to this. Words can be cheap, and no matter how confidently we speak of our beliefs or faith, we can negate our words by actions contrary to what we say we believe. Then, too, people look to our actions to see if they might trust our words. See St. Paul, “If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.” (I Corinthians 13:1ff) We don’t want to be noisy goings! But we don’t want to keep our mouths shut when using our voice can bring enlightenment, comfort, happiness, or even rescue. Or a warning! There are things we know that the rest of the world can do without knowing. But there are also things we know that can bring blessing or new, and needed, perspective and understanding to others. Sometimes people need to hear wisdom or experience or knowledge or love spoken aloud. The voice can cut and injure and destroy. But it can also build up and heal. If a touch or an action will do that, great. We don’t have to risk embarrassing ourselves! But sometimes things just need to be said, even if we can’t say them eloquently or the words are hard to form. Remember, too, that John the Baptist’s mission is ours, too. We are asked to point out the presence of God in the midst of a sometimes dark and cynical world, and that He once entered our world in our shape and form, enjoying the best of human relationships and suffering a tortuous death because of the fears of those who represented both Empire and the religious establishment. We are to use our voices to say that God is for the vulnerable and the outcasts and those who don’t always fit the mold of what some see as a well-ordered society. We are to use our voices to denounce injustice and untruth. And I suppose I should remind you that using your voice for the above doesn’t always get you reward points with those who like to abuse their power. John the Baptist spoke truth to power and ended up with his head on a platter! We will get—or we already have-- our energy and courage from that which we know in our deepest beings but cannot prove: That the One who has been before the beginning of the Universe and is behind all created things, is our light and our life. A light that continues to shine in our dark Advent world, that the darkness did not, and will not, overcome. That this One is everywhere in the world, and yet unseen. That this creating energy has become flesh like us and once dwelt among us, and as Resurrected body dwells with us still. We in Him and He in us. Testify to this to others. People need good deeds. They also need good news voices. . . . . Can we count on yours? The Feast of Christ the King

Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 26 November 2023 Today, we commemorate the Feast of Christ the King. This is a relatively new feast on the Church Calendar, instituted by Pope Pius XI in 1925. The historical context in which the pope introduced the feast was the militant nationalism that had been infecting Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and had been one of the major causes of World War I. Pius XI wanted to remind the faithful that as Christians, our highest allegiance – above any nation or government or leader – is to our Lord Jesus Christ, the King above all kings and the King of all Creation. The feast has spread from the Roman Catholic Church to other denominations, including the Anglican Communion. The Feast of Christ the King falls on the last Sunday of the Church Year. This serves to remind us that at the end of time, Christ will come in all his glory and power. As we prayed in the Collect, he will establish his rule as “King of kings and Lord of lords.” We have many examples of the kingship of Christ depicted in Christian art. The iconography usually has Jesus enthroned in glorious majesty and splendor and surrounded by a host of angels and saints. Sometimes, he wears a crown and carries a scepter as symbols of his royal authority. But there is another depiction of Christ the King, one that is ironic but, in fact, more familiar to us than the regal depictions. It is the image of Jesus hanging on the cross. Above his head is the inscription, INRI, the initials representing the Latin words, Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum, “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews.” It is the title that the Romans conferred on Jesus in mockery and contempt as they tortured and nailed him to the cross (John 19:19). But, for us, his disciples, this title is an expression of our faith, for Jesus is indeed our King. And whether it is the crucifix that hangs above us during our worship or the crucifix on the rosary in our private devotions, it is this image of Jesus the King that we behold in our daily lives. It is the image of a king who has emptied himself of all his power and glory and given up his very life for the sake of the world. It is the image of the Almighty God who has become one of us, a vulnerable human being, to suffer and die. It is the image of our faith and salvation. And this king who hangs on the cross, this king who has emptied himself of power and glory, calls on us to follow his example. We, too, are called to empty ourselves of power and glory. Last week, I was at an annual academic conference for religious studies. It is always a great pleasure to learn about what other scholars are working on as well as catch up with old colleagues and friends. The part of academic life, however, that I do not care for is the game of status. Scholars don’t make a lot of money, but – perhaps because of that – the competition for status can get pretty fierce. We judge ourselves based on the schools we attended, the number of publications and grants, and so on. I often wonder why we can’t just focus on our love of learning and teaching? Why do we become so full of ourselves? I’m sure this kind of game of status is nothing new to you. Whatever our professions, most of us have to deal with the competition for money, power, and status. It’s the reality of our society. And yet our Christian faith calls us to a different perspective and standard. Christ, through word and example, calls us to empty ourselves of all self-centeredness, to turn our attention away from our desire for money, power, and status, and to focus on others in self-denying love and service. The Kingdom of God that Jesus proclaimed while he was on earth was based not on power and glory but mercy and compassion. In today’s Gospel from Matthew, Christ calls on the faithful to love and care for those who are the most vulnerable –the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick, the prisoner (Matthew 25:35-45). He tells us that “just as you did to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:40). When we serve those in need among us, we are serving Christ in them. In the history of our faith, we have many examples of the saints who have heeded Christ’s call to humble themselves and serve others in sacrificial love. Last Sunday, we commemorated the Feast of Saint Margaret of Scotland, one of our patron saints. We have a chapel in the basement dedicated to her. Some of you may noticed that we recently brought up her portrait that used to hang there to Saint George Chapel. In the painting, she is holding a spoon, feeding a small child. The image is based on Margaret’s daily routine of feeding orphans and the poor before she herself ate. And she also washed the feet of the poor, following the example of Jesus. She may have been Queen of Scotland, born to extraordinary wealth, power, and privilege, but in her daily life she was first and foremost a humble disciple of Jesus. None of us here are royalty, though some of you may have royal blood. I know we have a parishioner here who counts Saint Margaret among her ancestors. There may be others of you who’ve done genealogical work and come across some royalty in your family tree. But whether we’re descended from royalty or peasants, whether we’re from privileged or underprivileged backgrounds, whatever the circumstances into which we were born, we share one thing in common. As disciples of Jesus, we are all called to follow his example of self-emptying humility and sacrificial love. We are called to live not for ourselves but for God and for others. So, on this Feast of Christ the King, we proclaim Jesus the Lord of Creation and Lord of our lives. We offer our bodies and souls to his service. May Christ the King reign in our hearts this and every day that we may carry on his work of love in the world. Saint Margaret of Scotland

Twenty-Fifth Sunday after Pentecost Sunday, November 19, 2023 +In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. At first glance today's observance of the feast of Margaret queen of Scotland might seem a little out of place here in Saint Mary's church in downtown Kansas City in the year of our Lord 2023. After all, outside of Scotland Margaret is not particularly well known, and apart from a beautiful window in the gallery to my left there is little historical connection between St. Mary’s and St. Margaret. So, who was St. Margaret of Scotland and what does she have to say to us today? Margaret was the granddaughter of the English king Edmund Ironside, but because of dynastic disputes she was born in Hungary, in the year 1047. She had one brother, Edgar, and a sister, Christina, and many people in England saw her brother Edgar as the rightful heir to the throne. In 1054 the parliament of Anglo-Saxon England decided to bring the family back from Hungary so that they could inherit the throne when King Edward the Confessor died, as Edward had no children. So, Edgar, Christina and Margaret were brought up at the English court under the supervision of Benedictine monks and nuns, who trained the young people according to the Benedictine ideal of a life of work and prayer. Eventually King Edward the Confessor died, and soon afterwards William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066 and claimed the throne for himself, so Margaret’s brother Edgar didn’t become king after all. Edgar and his sisters were advised to go back to Hungary for their own safety, but on the way their ship was blown far off course by a fierce gale. The trio was shipwrecked at the Firth of Forth in Scotland, a place that to this day is known as St. Margaret’s Hope. It is there that King Malcolm III gave them a warm welcome to his kingdom. …His court at Dunfermline was undoubtedly rather primitive compared to the English court that the family had known, but they were glad of his welcome and the hospitality and safety he offered them. Margaret was now about twenty years old; King Malcolm was forty, and unmarried, and he soon became attracted to young Margaret. However, she took a lot of persuading; as she was more inclined to become a nun, and Malcolm had a stormy temperament, despite his other virtues. It was only after long consideration that Margaret agreed to marry him, and their wedding took place in the year 1070, when she was twenty-three. In the end, although she was so much younger than him, she was the one who changed him; under her influence, he became a much wiser and godlier king. Although Margaret was now in a high position in society, and very wealthy according to the standard of the day, she lived in the spirit of inward poverty: nothing she possessed really belonged to her, but everything was to be used for the purposes of God. As Queen, she lived an ordered life of prayer and work that she had learned as a child. She was only the wife of the king, but she came to have the leading voice in making changes that affected both the social and the spiritual life of Scotland. She had this influence because of the depth of her husband’s love for her. Malcolm didn’t share his wife’s contemplative temperament, but he was strongly influenced by her godly character, so he tended to follow her advice a lot – not only for his own life, but also for the life of the church and people in Scotland. Margaret would begin each day with a prolonged time of prayer, especially praying the psalms and attending Mass. We’re told that after this, orphan children would be brought to her, and she would prepare their food herself and serve it to them (this is displayed in the painting of St. Margaret which is now hanging in the back of St. George’s Chapel.) It also became the custom that any destitute poor people would come every morning to the royal hall; when they were seated around it, then the King and Queen entered and ‘served Christ in the person of his poor’. Before they did this, they sent out of the room all other spectators except for the chaplains and a few attendants because for Malcolm and Margaret this act of charity was not about show but about service. Throughout most of history them majority of the women remembered as saints by the Church have been martyrs or monastics far removed from the demands of the world and the pressures of family life. Margaret, however, is remembered as having a happy family life. She had eight children, six sons and two daughters. Her oldest son Edward was killed in battle, Ethelred died young, and we’re told that Edmund didn’t turn out too well. But the three youngest, Edgar, Alexander, and David, are remembered among the best kings that Scotland ever had. David I, the youngest son, had a peaceful reign of twenty-nine years in which he developed and extended the work his mother had begun. The two daughters, Matilda and Mary, were both brought up under the guidance of Margaret’s sister Christina in the Abbey of Romsey, and both went on to marry into the English royal family. All of them we’re told, were imbued by their mother with a deep faith and a desire to follow Christ first. Margaret was not yet fifty when she died. As she lay dying, her son Edgar brought her the sad news that her husband and her oldest son had been killed in battle. Despite this grief, we’re told that her last words were of praise and thanksgiving to God, and her death was calm and tranquil. Margaret died on November 16th, 1093. A member of the aristocracy, she came into a position of great influence as Queen of Scotland, but she didn’t think she’d been given that position in order to lord it over others. Instead, she’s remembered as a person who spent her life serving others. It is here, in the fact that she is remembered for serving others that I think St. Margaret has something to teach us because despite being literal royalty Margaret was willing to give it all away for the pearl of great price that is a relationship with Jesus Christ. Everything she was and had was spent on building that relationship and the good works that flowed out of it. Margaret spent hours of her day in prayer. Like our Lord in his earthly ministry Margaret would withdraw to a deserted place to pray. Is that our habit? Do we make time to pray regularly, both in community at Church and on our own in a deserted place? For some people, the ‘deserted place’ might be a room in their house; for other people it might be a quiet office early in the morning; for others, it might be a quiet walk at some point during the day. For some it will be alone, for others it will be together with a spouse, or with the family as a whole. Regardless of how we do it…. is spending time in prayer deepening our relationship with Jesus, our pearl of great price, a priority? Margaret teaches us that if we want to be holy if we want to make a difference in the world this is where we must start. Because from that prayer flowed Margaret’s countless acts of service, her gifts of charity, her feeding of orphans and widows and the houseless they all came out of the love she had for God and for God’s people because that time with Jesus changed her. Although she was the Queen of Scotland, she saw no contradiction between being the Queen and serving at tables for the poorest of the poor. She understood herself first of all as a servant of Christ; everything else followed from that. Although I have no proof of it, I can't help but wonder if maybe that is why our predecessors in the faith here at Saint Mary's chose to honor an obscure Scottish Saint, with a beautiful stained glass window because they hoped that they and we like Margaret might be so changed by the relationship with Jesus Christ that is begun and nurtured in this place that our love would overflow in service to all those most in need around us. Are we living up to their hope? Are we giving everything to know Jesus and to serve God and his people? If the answer to those questions is no, then I encourage you here today to come to this altar to receive Jesus, the pearl of great price, in the sacrament of his body and blood and to recommit yourselves to nurturing your relationship with him in daily prayer so that you might be changed like Margaret and so that like her you might change the world. St. Margaret, Pray for us. +In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. Sermon for Pentecost 24 Pr. 27

St. Mary’s Episcopal Church November 12, 2023 Amos 5:18-24 Ps. 70 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18 Matthew 25: 1-13 I like preaching from the lectionary, because if I didn’t I would be preaching on variations of about ten sermons all of the time. The lectionary also makes me delve into the richness of the Bible while keeping my attention centered on specific passages. It is like eating at a restaurant that serves you a small portion of something on the menu before going on to the next small-portion dish. On the other hand, the “small portions” of Scripture served by the lectionary readings/lessons for each Sunday is still often far too much to try to “inwardly digest”, as the collect for next Sunday puts it. The lectionary also forces me to preach on texts that I don’t want to even put in my mouth and give me indigestion just looking at them! And then there are the Sundays which have more than one text that are unpleasant to look at and hard to digest—Today we have Three of them! An angry prophet tells those who can’t get out of ear shot of him that God “hate(s) (and) despises your festivals and take(s) no delight in your solemn assemblies.” Yeah, that is supposed to fly here at St. Mary’s! Then St. Paul, in his letter to the church at Thessalonica lays down Scriptural warrant for the Rapture—the idea, in case you aren’t familiar with it, that the literalists have that when Jesus comes back, those who are faithful will be swept up into heaven in the blink of an eye, leaving the rest of us dodging driverless cars on I-70, as they hang out with Jesus. Then Matthew recounts a parable of Jesus’ which says we had better have oil in our metaphorical lamps when Jesus shows up or we are going to be pounding on a closed door in the dark. I love the lectionary! Well. pause O.K. then! If I try to deal with all three lessons today we’ll all have indigestion! Let’s encounter the angry prophet, Amos, you are on your own for the others. Though I would be glad to talk to you about the others outside of the sermon. Amos, like all the prophets before and after him, was called by God to speak what God wanted to say to the King, government, and people of the divided nation of Israel/Judea. Like all the other prophets, he wasn’t a predictor of the future, except to tell people that if they didn’t stop ignoring God, or trying to be God, and failing to live by the principles set out in Torah, they were going to shoot themselves in both feet. Doom wasn’t inevitable, but actions have consequences! This role, naturally, did not endear people to prophets who were faithful to God. Old Testament scholar, Harrel Beck, once said that “the prophets were twice-stoned men. First, they were stoned on God when they delivered God’s message to the people, and then the people stoned them because of what they said! Unlike the other prophets, Amos was not a citizen of the country he was prophesying in. After the excesses of King Solomon, revolts against the crown erupted in Israel, splitting it into the Northern Kingdom, Israel, and the Southern Kingdom, Judea. Enmity existed between the citizens of the two kingdoms from thenceforth, despite common roots and common faith. Amos was a citizen of Judea, not Israel. He was a foreigner! Furthermore, he was not a “professional prophet,” he was a layman, not clergy of any sort, and was not of the elite of any sort—he was a “herdsman and a dresser of sycamore trees,” a common laborer. Israel, at the time, had not suffered the kind of political reverses that comes from being geographically located on the pathway of armies of some major players among the nations of that part of the world as Judea was. They were not under threat of invasion, they probably had a stable, perhaps prosperous, economy. Into this self-assured culture, Amos steps out of his pick-up in jeans and work boots and proceeds to lay into its citizens, in the name of God! Actually, he starts by laying into every known nation of the region with how they have offended God, before he tells the people of Israel that they were living high on the hog, caring nothing for the poor and vulnerable in their midst, in fact taking advantage of them to live high on the hog! He even calls the women Israel “cows of Bashan, who oppress the poor, who crush the needy.” He wasn’t invited back to coffee hour! He actually didn’t have anything kind to say to anyone! In this morning’s lesson he confronts the “church members” in their self-assurance about Israel’s destiny. “Alas for you who desire the day of the Lord.” “The Day of the Lord” was understood by Amos’s audience to be a time when God would vindicate their nation, who would destroy other nations who were possible 1adversaries, and they, the chosen, would be dancing in the streets. Amos gives an alternative view: The day of the Lord will be “darkness, not light, and gloom with no brightness in it.” He gives a darkly comical account of what will really happen. “It will be as if someone fled from a lion, and was met by a bear; or went into the house (maybe to get out of the sun or rest from running from a lion?) and, resting their hand against the wall, were bitten by a snake!” If God shows up in their midst, He won’t be happy! Since we are to read the Bible as a living document, not a relic from the past, we are always being invited into the world of the Bible to find that that world is really the one we are living in now. That being true, what are we to make of Amos addressing us as he addresses the citizens of ancient Israel, “I hate, I despise your festivals, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies . . . take away from me the noise of your songs (“The word ‘song’ -shir- is nothing less than the title of the book of Psalms!)” – Maryann McKibben Dana Feasting on the Word, Vol. 4, p270) --I will not listen to the melody of your harps.” I rather like our solemn festival masses, and the beauty and majesty of our music. The sung Psalms—beautiful!! We don’t have a harp, but we do have an organ. Our worship space is a place of sacred beauty. What is Amos telling us? Well let’s not turn off the lights and go home! With a little background from the scholars who dig around in such things, we can infer that the people of the northern kingdom could have been celebrating their prosperity by confusing it with God’s providence, in essence saying, “Thank you, God, for making us exceptional.” Or maybe they were saying something like, “Look at how we adore you, God. Look at the lengths we go to worship you!” OR, “Look at the size of the gifts we bring you!” Things were going well for them, and they were resorting to flattery and bribery of God to keep things that way! To look at the character of God through the whole sweep of the Bible—and that is something we have to remember to do, rather than judging God, and ourselves, by fragments of Scripture—it is sound to say that God isn’t interested in being impressed—He doesn’t need, or want, the flattery of mere mortals, and how can you bribe Someone who is the source of everything? What God wants is to be in relationship with us. “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind,” this is the first and great commandment.” Love is a two-way street; we are to love God because God FIRST loves us—desiring the best for us (which isn’t necessarily always the easiest or the most comfortable). AND he desires that we take seriously our being in relationship with others. “And the second is like unto it: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” In fact, the heart of the “Law” within the Jewish Scriptures, the Old Testament, affirms that to love God is to love others, and that when we love others we are loving God. And when we grasp that God loves us in spite of who we are it is easier to love others. In fact, out of His love for us God will give us the wisdom and the energy to love others. Our love might be, probably will be, imperfect, flawed, and insufficient, but it will give us, and those whom we show love to, a glimpse of what the Kingdom of God is, and will someday become. A prophet like Amos reminds us, however, that God, even though steadfastly loving, can be angry and fed up with us and what we do to others. The people Amos addressed are self-satisfied with their worship rituals: both ceremonies and gift-giving. They are proud of their performance of impressing God even as they ignore the sick, the poor, the vulnerable, and the hungry. Amos tells us, “Don’t be those people!” But he goes on to say, but “let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream!” Justice is more than random acts of kindness. To champion justice, which is basically see that others are treated as we would like to be treated requires more than one on one interaction. In involves such things as who we vote for and the causes we work for. I like to think, and I’m willing to bet, that those who love to use their gifts of music and ceremony here at 13th and Holmes are not creating music and beauty to impress God, but to celebrate the relationship they have with God, acknowledging His love and presence in their lives. And those of us listening, watching, and participating within our own abilities, as we come together for worship each time we gather in this place, are doing the same. And furthermore, the gifts we give of time and treasure to support this old church and its traditions, as well as the mission of this parish, diocese, and national church, are truly thank offerings instead of bribes. That doesn’t mean God is always pleased with us, or sees us as doing all that we can, because most of us probably aren’t. I know I’m not. But, then again, “doing all we can do” is not necessarily what God desires from us. We don’t gather here to get a “to do list,” which would be a “one more thing to do of many” list. Another stone thrown to us when we are trying to swim in the challenges and stress of our lives. What God desires is to allow Him to love us and to love others through us. He will work out the details as we go along. We show up here, not to get a “to do” list, but to be empowered, through worship, prayer, and sacrament, to hear whatever God speaks to us in our hearts and minds about, and follow Him through any door He opens. And any time we find ourselves patting ourselves on the back for doing that, let’ go back and read Amos! Feats of All Saints

Sean C. Kim St. Mary’s Episcopal Church 5 November 2023 Today, we commemorate the Feast of All Saints, honoring all the saints who have come before us in the faith. The saints are an integral part of our public worship and private devotions. Here, at St. Mary’s, we have our patron saints, whom we name at every Mass – Blessed Luke, Blessed George, Blessed Cecilia, Blessed Therese, Blessed Margaret, and, of course, the Blessed Virgin Mary. And throughout the year, we commemorate the saints on our church calendar during Daily Masses. Today, after the sermon, we will chant the Litany of the Saints. Beginning with Mary, the Litany will present a kind of panoramic history of two millennia of Christian history, calling out the names of holy men and women from many different eras and places. So, you might ask, especially if you’re from a more Protestant background, why all the focus on saints? Why all the services dedicated to the saints? According to today’s Collect, we remember and honor the saints because they present for us models of faith: “Grant us grace so to follow thy blessed saints in all virtuous and godly living.” Follow thy blessed saints in all virtuous and godly living. When we think about the saints of old, their extraordinary achievements seem beyond our reach. Most of us will never be called, as Perpetua and Felicity were, to pay the ultimate price and suffer martyrdom. Most of us will never be called, as Columba, Aidan, and Patrick were, to become missionaries and preach the Gospel in hostile, foreign lands. Most of us will never be called, as Francis and Clare of Assisi were, to vows of absolute poverty. But whatever our personal circumstances may be, we are called to the same life of “virtuous and godly living” as followers of the same Lord Jesus Christ. We could spend a lot of time discussing what “virtuous and godly living” means, and we may have different opinions about what is virtuous and godly. Ancient theologians and philosophers used to compile different lists of virtues: the four cardinal virtues, the three theological virtues, the seven capital virtues, and so on. And, of course, there are plenty of lists of vices as well – and they tend to be more interesting. The fact is, we don’t need a long list of virtues to live a “virtuous and godly life.” In last week’s Gospel reading, we read about the Pharisee asking Jesus which of all the commandments is the greatest. Jesus responds with what some call the double love command, also known as the Summary of the Law: love God and love neighbor. All the laws and commandments are rooted in these two. Or to put it another way, all the various virtues emanate from loving God and loving neighbor. To turn again to today’s Collect: “Grant us grace so to follow thy blessed saints in all virtuous and godly living, that we may come to those ineffable joys which thou hast prepared for those who unfeignedly love thee…” Unfeignedly love thee. The saints are all about love – loving God and loving neighbor. That’s why among the saints’ names on the Litany, we have Fr. James Stewart-Smith and Fr. Edwin Merrill. Fr. Stewart-Smith and Fr. Merrill were both beloved priests at St. Mary’s. They’re the two priests whose portraits grace the back wall of St. George Chapel. This past Thursday, on All Souls Day, we celebrated Mass at Forest Hill Calvary Cemetery. And we paid our respects to Fr. Merrill and Fr. Stewart-Smith, who are laid side by side in the cemetery. I took a photo between the two tombstones in the hopes that some of their saintliness might rub off. Fr. Stewart-Smith served twenty-three years as rector from 1891 to 1914, and Fr. Edwin Merrill, for 35 years, from 1918 to 1953. Between the two of them, they served St. Mary’s for basically the first half of the twentieth century. But we remember and honor Fr. Stewart-Smith and Fr. Merrill not just for setting records in terms of the length of service but because of their deep and abiding love. They loved God, expressed through their life of prayer and worship. Everything they did was grounded in their profound spirituality. And they loved neighbor, establishing numerous ministries for the poor and needy. One of the tributes to Fr. Stewart-Smith at his death described his life as “a labor of love…walking among the lowly, the poor, the distressed and the fallen as a ministering spirit to relieve comfort and to lift up.”[1] Fr. Stewart-Smith and Fr. Merrill are modern-day, local saints who have bequeathed to us at St. Mary’s a powerful and beautiful legacy of love. Fr. Stewart-Smith and Fr. Merrill, and all the saints that we name on the Litany are long dead and gone. But they are alive to us not just in memory. We are united in Christ as one body. Again, to use the words of today’s Collect, we are “knit together in one communion and fellowship in the mystical body of Christ our Lord.” We, the living and dead, are all united through faith in Jesus Christ. And we experience this unity with Christ and the saints most fully in the Eucharist. In the sacred mysteries of the Eucharist, the veil between heaven and earth disappears, and we are joined by the saints and all the citizens of heaven. So, dear sisters and brothers, on this happy feast day, we celebrate all the saints. We hold up these models of embodied love to remind and inspire ourselves of what it means to live as followers of Christ Jesus. And as we gather at the altar, we join our voices with those of all the saints in our eternal praise and worship of the Lord our God. [1] W.F. Kuhn, “Tribute to Fr. Stewart Smith,” The Kansas City Free Masonry, August 21, 1915. Pentecost XXII

Matthew 22:34-46 St. Mary’s Episcopal Church Sean C. Kim 29 October 2023 In today’s Gospel reading from Matthew, we have what is known as the Summary of the Law: Hear what our Lord Jesus Christ sayeth. Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like unto it. Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets. Sound familiar? Well, you just heard at the beginning of today’s service. The Summary of the Law is an integral part of the Anglican tradition of worship, and here at St. Mary’s, you hear it at every Mass. As with many aspects of our liturgy, it is biblically based. In today’s reading from Matthew. Jesus is in the middle of a confrontation with Jewish leaders, who are out to test him. A lawyer, a Pharisee, asks him, “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest” Jesus responds by selecting two passages from the Hebrew Scriptures, the Torah. The first is Deuteronomy 6:5, and it is part of what is known as the shema: “Hear therefore, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.” The shema is an ancient confession of faith for Jews, and it is still used in worship today. But Jesus doesn’t stop there; he couples the shema with Leviticus 19:18: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” Judging from the silence that follows, Jesus passes the test. We are told that from that day on, no one dared to ask him any more questions (Matthew 22:46). The Summary of the Law is a constant reminder of what it means to be a Christian and what we value most in our faith. All the laws and commandments can be boiled down to loving God and loving our neighbor – in Jesus’ words, “On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.” Loving God and loving neighbor are not only the two foundational commandments on which our faith rests; they are also inseparable and interrelated. Our love for neighbor flows out of our love for God. We cannot say that we love God if we do not love our neighbor. Of the two commandments, however, we tend to hear and talk a lot more about loving neighbor than about loving God. Loving neighbor is a favorite topic of sermons. And around Christmas time, which is just around the corner, we hear the message not just in church but in our society at large. Think of all the feel-good movies and TV shows, and the calls for charitable giving during the season. We can never hear enough about loving our neighbor, but, the fact is, we don’t hear as much about loving God, even in church. I think part of the reason is that we don’t always know what loving God means. We believe in it, but we wonder how we go about loving a God who is transcendent, beyond the reach of our five senses. We certainly cannot see or touch God, and we cannot put our arms around God and say “I love you” as we would a person. So how do we love God? Well, the Summary of the Law provides a key. In fact, it lays out a three-fold approach to loving God – with all our heart, with all our soul, and with all our mind. To begin with, we love God with all our heart. The Hebrew word for heart has a different sense than in English. We tend to associate the heart with emotions, but in Hebrew the heart has more to do with intention. It is “the center of a person’s willing, choosing, doing.” So, to love God with all our heart means to turn our hearts, our intentions, away from the world and ourselves to God. It is placing God above our personal interests and desires. Second, we love God with all our soul. We pour out what lies deep in our soul to God through prayer. Whether we do so in private or in public worship, prayer is our main line of communication with God. Through prayer, we give thanks as well as present our petitions and intercessions, and we listen to God’s voice and discern God’s will for our lives. Finally, we love God with all our mind. For the Jews, loving God with their mind meant studying God’s Word as revealed in the Torah. For us Christians, it is the Bible. Some of you may be familiar with the daily devotional called Forward Day by Day. We have copies on our welcome desk in the Parish Hall, if you’d like to pick one up after the service, and it’s also available online. Forward Day by Day is published by the Forward Movement, an Episcopal organization, which recently did a survey of Episcopal churches on various topics, and it found, to no great surprise, that we as a denomination don’t read or know our Bible as well as other denominations. Perhaps it’s our focus on liturgy; I know Roman Catholics don’t do too well on biblical literacy either. But for whatever reason, we are not reading God’s Word as we should. If I might share a personal note with you, actually a recommendation, I have found the Daily Office of Morning and Evening Prayer to be a rich resource for both prayer and Bible study. I’ve been an Episcopalian for almost twenty years, but it wasn’t until I began the ordination process a few years ago that I discovered what a treasure the Daily Office was. Praying Morning and Evening Prayer every day is a source of great strength and spiritual growth. I love the rhythm and the discipline that it provides. And the Daily Office takes us into prayer as well as Bible study since both Morning and Evening Prayer have selected readings from the Psalms, the Old Testament, and New Testament. The Daily Office will basically take you through the entire Bible in three years. So, if you are not praying the Daily Office already, I would highly recommend it. Historically and theologically, the Daily Office is the most distinctive aspect of Anglican spirituality. And these days, there are all sorts of Internet programs that make it convenient and easy to pray the Daily Office. Dear friends, as we pray and study Scripture, we are obeying the greatest commandment to love God with all our heart, with all our soul, and with all our mind. And grounded in our love of God, we will be able to love our neighbors as ourselves. On these two pillars of love rests our calling as followers of the Lord Jesus. And during this time of war and violence, strife and division, we have a lot of work to do in living out our calling. So, let us pray as never before. Let us immerse ourselves in God’s Word. Let us go forth into the world proclaiming Christ’s Gospel of love. Amen. |

The sermons preached at St. Mary's Episcopal Church, Kansas City, are posted here!

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

To the Glory of God and in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Address1307 Holmes Street

Kansas City, Missouri 64106 |

Telephone |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed